Back to main interview page

|

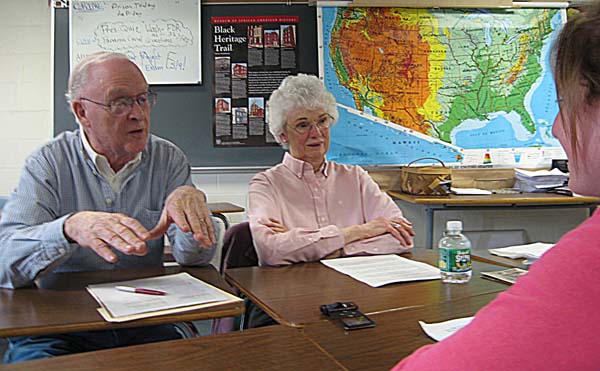

Maurice and Matt Whittaker May 8, 2008 |

|

|

|

Memories of the Hurricane of '38 |

Mr. Maurice Rockett was born in Boston City Hospital on May 22nd, 1921. He grew up in Sharon and Dorchester and remembers his high school experience in a graduating class of about thirty people fondly. Mrs. Grace Rockett grew up in Medford with her parents and her sister. Mr. Rockett remembers the Hindenburg crash and the Hurricane of ’38 in vivid details as well as visits from the iceman and other small events. He recalls that back then people walked and biked everywhere; there were very few cars. Mr. Rockett thinks that by just going back to what times were like in the 30’s we can solve our energy crisis today.

Mr. Rockett: What we thought we’d do, with your permission, is to have some introductive remarks. Kind of get the show on the road, alright? And then you can pepper us with your questions.

Q: Okay.

Mr. Rockett: But please don’t compare us with the lecture series the professor has.

Q: (Laughs)

Mr. Rockett: We’re not trying to compete with him.

Q: Got it. We just have to read off something first.

Mr. Rockett: Alright, Boston City Hospital…

Mrs. Rockett: (Stops Mr. Rockett)

Mr. Rockett: What? You have some questions? Go ahead.

Mrs. Rockett: Will you close your mouth and wait your turn?

Mr. Rockett: No, my turn!

Q: I just have to state...we just have to start with one thing.

Mrs. Rockett: No, you are the onlooker; they are the ones in charge.

Mr. Rockett: Go ahead.

Q: Okay. So this is Naomi Rosenhaus.

Q: And this is Laura Wu.

Q: And we are interviewing Mr. and Mrs. Rockett on May, 8th, 2008 for the Wayland High School History Project. Please state your name.

Mr. Rockett: Maurice Rockett.

Mrs. Rockett: Grace Rockett.

Q: Do you want to start with your introduction?

Mr. Rockett: Yes, Boston City Hospital, May 22nd, 1921, a bouncing baby boy, me! So, if you’re good at math, that means I’m going on eighty-seven, and still around, and still kicking. At that point we were living in Dorchester, which is a part of Boston. And I don’t remember too much of those days because that’s going way back, but I do remember going to a high point and flying kites with my father. You could look out and see the ocean. I had bronchitis, so I missed a lot of days in school.

Q: When you were young?

Mr. Rockett: Yeah, so I didn’t get through the first grade. I had to repeat it, but I didn’t repeat it in Boston. One day while sitting on the side curbing on the street, the ice man came by and hit me in the face with a chunk of ice. Now “ice man” probably means nothing to you, but in those days we didn’t have electric refrigerators. A man came to the house, looked up at the house in the window, and there would be a sign. It would say, “Ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five.” That indicated what size of a piece of ice you wanted, so he’d take it out the bigger piece and bring it into the house.

Q: So you had ice-boxes?

Mr. Rockett: Yeah, we had an ice box on top. Now when I lived in Sharon, they would go into the lake with big saws and saw the ice, and wheel it across the road, and put it in a big wooden building, and cover it with straw. And that would stay like that all during the summer. So the basic supply of ice for the customer was in that ice house. Now because of my health problems, someone suggested, could have been a doctor, that we go somewhere where the air would be better than city air. So we went to Sharon, and Sharon was out in the sticks, it was rural. You call this semi-rural, whatever the hell that means. This is rural, okay, out in the sticks, and the advantages of Sharon was we had good rail transportation from Boston to New York, and a lot of people who lived there to commute back and forth. While in Sharon, I went from grade one through grade twelve. And Sharon had good schools. Now, I don’t like to say that to Wayland people because you have good schools just like about a dozen other towns around, okay, so the cat’s out of the bag there, and it’s not unique. If you were to have gone at that time to the Wayland High School parking lot, you would have seen two cars for students. Two cars! One car was given to the student by his parents, and the other was used to deliver groceries, and that’s how he made his money because the people didn’t have cars to get to the stores. There were no malls! Okay? And if the store is two miles away that’d be a little far to walk and come back with a load of groceries, so you’d call to the store, and they would deliver. Now today that’s like a delivery service, but it was a way of life. So this fella, the student, made his money by coming after school and chauffer…taking the groceries around to people who had called in.

Q: That’s a good job!

Mr. Rockett: Okay? Now maybe some of the teachers had cars, but there wouldn’t be many. So the means of transportation was your two feet or a bicycle. Could you handle it?

Q: No. (Laughs) How many kids did you think there were?

Mr. Rockett: In school? Well the population of the town was 3,000. I would say in the school if it was maybe 100, it’d be a good number.

Q: Wow, that’s so tiny.

Mr. Rockett: Yeah. So my senior class was, I’d say, thirty, just as a ballpark figure. When I grew up in Sharon, I had a brother, a baby brother, he was two years younger, and we both slept in the same bed. And we had the one bathroom, and we didn’t have central heating or anything, we had a coal furnace downstairs. So someone would come up with a truckload of coal, and ship it in the cellar, and it was stored in the cellar. So if you wanted to heat the house, you take the coal, shovel it into the furnace, and that kept the fire heating the house. Now in the morning there was only one place where the heat came up, and that would go towards the stairs that go up, heat rises, it would go upstairs, but in order to keep the warm we took turns standing on the register to get dressed. My mother used to do the laundry on a scrub-board. You know what a scrub-board is?

Q: No.

Q: Yeah.

Mr. Rockett: It’s something about this big and has the metal on it…

Q: Oh yeah, yeah.

Mr. Rockett: You scrubbed the laundry and did that back and forth with the soapy water down below, and that’s how they washed. The next job I didn’t like was cleaning rugs in the spring. I seemed to get stuck with that. So my mother would take wet tea leaves and sprinkle them all over the rug, okay? And I would hang it over two clotheslines, and I’d get this beater and I’d go, “Whack!” So then all the dust would come out like a smokescreen! So that would take at least an hour or two to take care of. Moving on for family life, we didn’t have TV. It was an unknown. Entertainment was listening to a radio, and there were all sorts of radio shows, especially on Sunday. Which it would fall and we would sit down as a family, and listen to the radio. And that was it.

Mrs. Rockett: But there were daily programs on for children because I grew up listening to Don…what was it? No…I’m sorry.

Mr. & Mrs. Rockett: “Where the Hudson High Boys show them how we stand!”

Mr. Rockett: C’mon! And he was singing for Wheaties “Wheaties! Don’t you try Wheaties? The best breakfast food in the land!” My father in the beginning used to always buy Essex, which gave him trouble, so we call it an “Ass-ex” not an “Essex.” So in order to start it there was a crank in the middle. You’d have to go down and crank it like that, and turn over the engine. Well unfortunately, every now and then, the thing would kick back, so it would break your right forearm. You had to be very careful; it was a dangerous thing to do. So that’s how they started the car. Then he moved to a Chevrolet, so we’re really going up the class. Now in Sharon, about a quarter mile away was the railroads. I said that before, they went from Boston to New York. And Canton Junction, which was a little south of us, and Foxborough, which was north, there was an elevation. And the train would hit that at night, about two or three in the morning, and you know (makes train noises). It would keep that up for about a half an hour. You’re trying to sleep. Happy day! Now we always called the train the “Choo-Choo.” And that’s why it was a “Choo-Choo” because of the “Choo-Choo.” Now with the coal burning, emanating from the smokestack was cinders, and all the cinders would fall on the sides. That sounded bad but the cinders were a terrific fertilizer for low-growing blackberries and blueberries. So many times I’d go up and pick them around house to house and sell them, and that’s how I made some money. The only problem with the blueberries was I put the damn things in a milk-bottle, and by the time you got around the houses, the milk-bottle started to sweat. They’d say, “Oh we can’t pay you twenty-five cents for that! They’re all wet!” So you’d have to bring the price down to, say, fifteen cents. And so that’s how we did make some money. Another aspect of school was called grammar school. Students were at the school until the eighth grade, and if they wanted to, they could call that the end.

Q: Wow, what did they do after that?

Mr. Rockett: Well, try to find a job, which there were none.

Mrs. Rockett: Very menial jobs.

Mr. Rockett: And as far as sports went, there was the Red Sox, and the Red Sox, by the way, were not what they are today. They got 15,000, “Wow-ee-boy!” Boston Braves, and the Bruins, now you went to the Bruins, up in the balcony where we sat, it was 75 cents or a dollar, the first two or three rows were common did by those from east Boston. And they would send over people, and they would put one at each end of each row. Now if you tried to get into that row, you wouldn’t walk out of the place. So everyone realized that. They were in charge! Even though they weren’t part of the guards, they were in charge! The next was the Boston Redskins, we had professional football. Now when they gave up in Boston, where do you think they went? Did you ever hear of the Washington Redskins?

Q: Yeah.

Mr. Rockett: They used to be the Boston Redskins. So we used to watch the Redskins play in Fenway Park. Now you’d see an All-Star game in Fenway Park. Then we had wrestling in the arena. The arena is now where Northeastern plays their basketball and hockey. Oh by the way, there were no places around to play high school hockey. Everyone had to go to the arena.

Q: Yeah they have to do that now.

Mr. Rockett: Occasionally the team from Walpole would come to Sharon and they would play scrubs against us to get practice in. And we had a good hockey team. Two or three Canadians, and we had a French school-van, and the teachers, called brothers, were all driven hockey players. They would just fly by you. So they would help us in our hockey and how to play, and we had a pretty good team. And finally there was college hockey played at the arena. So BC and BU had teams. Now whether Northeastern and Harvard had teams, I can’t say for sure. So those are the sports in the professional category at that time. As far as clothing went, we pretty much wore what you do today, pants, a shirt, and shoes, the whole thing. But, we generally would buy them oversize, so if you got a sweater as a freshman, you kept letting it down so by the time you were a senior, it’d fit. And a lot of clothing was hand-me-downs, from brother to brother, sister to sister, or family to family. So they might have been sewed or patched or things like that, but that’s the way things went.

Mrs. Rockett: That’s how my hand-me-downs went.

Mr. Rockett: My greatest memory was on May 6th, 1937. We were out in the playground, and we heard this noise. And we were thinking it was airplanes; airplanes were…whoa. But it didn’t sound like an airplane, and you couldn’t say, “Come in ma,” because we didn’t think of spaceships. What the heck is going on up there? And it was very cloudy, and all of a sudden this dark object came out of the mist, and it looked like a big whale. It was a German dirigible, called the Hindenburg. Well later on that day it landed in New Jersey, and it crashed and the whole thing burned up. One of the reasons that it crashed and burned up so quickly was because the United States wouldn’t give Germany the needed hydrogen gas, they had to use a more flammable product. It was a real disaster, and the person on the site who called it in really gave a terrorizing rendition of what took place. He was practically screaming in his recitation of what happened that day. So that was my greatest memory of what happened for high school was the Hindenburg flying over. Grace?

Mrs. Rockett: Would you rather ask questions, or would you like a dialogue like his?

Q: Yeah maybe we should start to ask these questions.

Q: So Mr. Rockett, if you were born in 1921, you were about eight years old or so in 1929. Do you remember anything about the stock market crash that year?

Mr. Rockett: No. You had to remember in those days people didn’t buy stocks, it was nothing like today. A few people, you had a million shares transacted you probably would say “Wow.” Today it could be fifty or sixty million. There’s no comparison. People didn’t have the money to buy the stocks. So we couldn’t care less about the stock market, it was the news, sure. But most people just lived in genteel poverty trying to get through day to day. We knew…well as far as the depression went, we were already in depression because we didn’t have money to buy things. Like today, you don’t get things, you get everything. That’s the difference.

Q: What about you, Grace? How old were you?

Mrs. Rockett: I was only four, so I remember zero. Well, I don’t remember because that’s too long ago. Talking about hand-me-downs, my sister and I had a cousin, she was an only child, and her mother worked, which was very unusual. But her mother was a widow, so she lived at home with her parents, my grandparents, and they took care of my cousin. But if my cousin wanted the moon or the stars, my aunt would try and get it.

Mr. Rockett: No denial!

Mrs. Rockett: She had very nice clothes, and my sister and I would have a big discussion, “When do you think we’ll get that dress?” And, “I’m gonna wear it first.” We argued constantly about who was going to wear what because we were about the same size as teenagers. But my father was on the fire department and he was on the list to be promoted, and at that time, and even now, police and fire in Boston were supposed to live in Boston. So we had to move from Medford, where we were living because my aunt was living right across the playground, and my mother’s sister and my father’s sister were right across the street, and it was just all family. So we were the first to break away, and it was as if we had gone to, say Worcester, because…

Mr. Rockett: Worcester, by the way, was close to the Pacific Ocean. You have to understand that.

Mrs. Rockett: Well, when we were getting married, because we would be living in Pennsylvania, and I said to her, “The world doesn’t end at the end of Massachusetts! It goes on!” But she wasn’t too happy. But getting back to a young age, I wasn’t really aware of any denial because we had the food that we always had. For breakfast we ate oatmeal, and if you didn’t eat oatmeal you ate shredded wheat or plain Corn Flakes or very seldom you got bacon and eggs. We were in a really tight community. We had a small lawn, it wasn’t even as big as this room, probably half of it, and I think the back may have been as big as this room. But there was a clothesline, and there was something else, they had chairs to sit outside. They weren’t interesting anyways.

Mr. Rockett: Let me interrupt with something before I forget. When you said, “eggs,” we had a half a dozen hens in the backyard. And every now and then we would point out that hen is ready to eat. So what my father would do is grab the hen by the neck, bring it onto a stump, and chop the head off. Then he’d let it go, and we’d all gather around and watch the hen run around! The headless hen! We thought that was a great show! (Laughs)

Q: So is that one of your favorite sources of entertainment?

Mr. Rockett: I also had the job of cleaning out the hen house. It’s almost like Paul Revere’s horse residue on Beacon Hill, you know, if never left.

Mrs. Rockett: Well, you know, we weren’t as countrified as he was. My father would take public transportation to work…the automobile registration ended November 31st, so January 1st the car went into the garage and we didn’t see it again until April.

Mr. Rockett: And then they get a credit on their insurance.

Mrs. Rockett: They would cancel the insurance, and they would also cancel the registration so you would get a cheaper rate starting out in April.

Mr. Rockett: We’re gonna take your car away!

Q: (Laughs) Please don’t!

Q: What kind of public transportation did you use?

Mrs. Rockett: It was the T.

Mr. Rockett: What you have today.

Mrs. Rockett: The Redline came to Dorchester.

Mr. Rockett: The horses were gone by then.

Mrs. Rockett: It wasn’t as extensive as it is today…

Mr. Rockett: What was it, a nickel?

Mrs. Rockett: I said extensive.

Mr. Rockett: Oh.

Mrs. Rockett: It was ten cents, and when we got in high school, both my sister and I elected to go into Boston to the high school in there. And we would have student tickets that were only five cents, and that was inexpensive. But my mother didn’t drive, so we walked to the store, and he says it would be too far to walk with groceries. Well, let me tell you that I walked with groceries plenty.

Q: (Laughs) She’s stronger than you!

Mrs. Rockett: Well, girls were supposed to do those things.

Mr. Rockett: A lot of women didn’t drive, period, because they felt it wasn’t a womanly thing to do. They didn’t vote for awhile either.

Mrs. Rockett: My mother didn’t work because married women had a hard time getting a job. In fact, if a teacher was going to get married, that’s the end of your job. We just didn’t have that many extras. In other words, the most important thing to buy was the newspaper, so we had three newspapers that came to the house every day. My father liked one, my mother liked the other, and we got one in the morning. They would deliver to the door; I remember the mailman coming twice a day. Now you’re lucky to get it once a day. But things were different in the summertime because my grandparents had bought a summer cottage, and we all lived: the two uncles and my family. Well the two uncles had families too. It was a duplex house, and my mother’s brother and his family were in one side and she and her sister and her family. But there were only four children and four adults, so we weren’t in the house that often. But the big thing was: this aunt having the job that she did, and she had married again, and her husband was employed all through the Depression, so we thought they were very rich because of the food that she would buy. And it was painful in the summertime because we had one table, and the four of us would be here and the four of them would be there, and we’d be looking over to see what they were eating.

Q: That’s painful. Did you ever eat Spam?

Mrs. Rockett: Yes.

Mr. Rockett: Not too often.

Mrs. Rockett: No, that wasn’t a favorite in our house, but we did have it.

Mr. Rockett: There was one thing about foods, they had Oleo in those days, which was obviously less delicious than butter, but it was white. So when you bought the yellow, you got a little pellet like that and you put it in the middle of the white, and you mash it like that for about an hour to work it all the way through to make it yellow, so that was a job that nobody liked.

Mrs. Rockett: Oh, I usually got stuck with that. As far as food was concerned, I don’t remember being denied anything because I hated it; we ate any of the food.

Q: Did you grow and can foods?

Mrs. Rockett: No. Not my family.

Mr. Rockett: If we were poor, we didn’t look at it that way. We just thought that that was the way things went.

Mrs. Rockett: But when we left the house in Dorchester and went to the cottage and stayed there for two months, two and a half months, we didn’t have any land around the cottage to grow anything. And every time we’d go home in the fall, the lawn was a wreck because you weren’t there to water it. So, things like that.

Q: And over the summer, you had your sister. Did you have cousins too?

Mrs. Rockett: Yes.

Q: Did you play any games?

Mrs. Rockett: Well we had paper dolls, and there was a celluloid doll that was probably about six inches tall, and then you’d try to make clothes for it. The arms didn’t move, the legs didn’t move, it was just a blob. And at that time we’d say it was Chinese or Japanese done. The paper dolls were in the newspaper, but you could buy the coloring books. They would have different paper dolls in different outfits, so you would very carefully be cutting and that would keep you occupied all day. And on Sunday it was an argument: who was going to get the paper doll, because they had one in the comics every Sunday.

Mr. Rockett: In those days we didn’t call it “the comics;” we called it “the funnies.”

Q: I call it “the funnies!”

Mrs. Rockett: We used our imagination. There were plenty of big, bold as I’d call them. The girls, what we’d do is we’d pick up different ones and then we would outline them on the ground. And this was our house, and we’d have a living-room, and a dining-room, and a kitchen. And then we’d pick up different things from the tide-line that had floated in from the ocean. Bones and shells and these were our serving-plates. We’d have a bone that some dog had probably chewed on and the knobs on the bottom, that would hold the vase, and we’d get weeds and put them in the empty end of the bone. Then there was another thing we did was make brick powder. You’d spend days going around, trying to find the right stones or bricks. You had to have a pounder. You had to have a table. You’d get a rock that’d have a flat side, and you’d get a pounder that’d fit in your hand and you’d sit there and pound until you pulverized it. And then you’d put it in a jar, or my cousin had a stem glass that the base had broken off, and that was still on the wall when he went away to the war. And when he came back, it was still there. You didn’t use coal because when you pulverized that it would gravitate and it would spoil all the other colors. They do it with colored sand now.

Q: So it’s for decoration?

Mrs. Rockett: Yeah. That was another fun time. And then we’d have a mixed “hide and seek” game. The boys always found these places you’d never think to look for. There were many tears when no one would come to find you (Laughs). And we also had tag, and the boys always played the baseball, but it was all pick-up. There was nothing planned. Out on the street there weren’t any cars, and we waited for the policeman to come every night because he had to bring in the box. And he’d come on his beat; he’d be walking.

Mr. Rockett: Was it gas streetlights?

Mrs. Rockett: No. I don’t know if we had any streetlights down there. But we knew him; his name was Bob, and, “When’s Bob coming?” And the ice-cream man would come, and sometime you had money for it, and sometimes you wouldn’t. And as far as getting food when we were there, there was a truck that came with vegetables and fruits, and a bakery came with all the goodies.

Mr. Rockett: A milk-man.

Mrs. Rockett: And of course the milk-man, and the ice-man. On Friday, a man came in a red truck, it was a small, red truck, and he would open up the back, and I was always fascinated because he had a refrigerator in there. And he had scales, and he would lower the back and it was a cutting-board, and you would order your meat and he would cut it and bring it to the house, and he would also carry fish on Fridays for the people who wanted that. You didn’t have to leave that area, that house. My mother, I think she never went any place. She just sat, but we were all swimmers and we enjoyed that part of it, and it was like one big family. Everybody knew everyone else, and that was just our favorite time of year.

Q: So, did you guys have any pets growing up?

Mrs. Rockett: No.

Mr. Rockett: We had dogs. We had one large police dog, and he went through the screen-door two or three times, so we got rid of him. And then we had a beagle, and every dog that would come by, he’d want to fight, even though he’d get beat. So one time, some people who did hunting said, “Can we borrow your dog? Let’s see if he can point.” Point for a beagle was if you went out, and there was a quail or something out there, he’d stop and go like that (makes pointing gesture). Well he didn’t do that, he ran after the quail, and the damn thing always got away, so I said, “Forget it!” We never had cats, it was just two dogs.

Mrs. Rockett: Well we had a cat, and I had forgotten that. He belonged to my sister’s girlfriend. She had a younger sister, and she would always grab the cat by the neck. So the cat would come to our house and cry at the door until my mother let him in. And he’d just run down the hall to the kitchen because he knew that’s where she’d give him milk. And we ended up with the cat because the cat wouldn’t stay home, and every time we’d call and say, “The cat was at our house.” Apparently the parents’ got sick and tired of hearing this so they said, “Why don’t you keep the cat?” And it turns out I was allergic to it. One night I was trying to do something with my father’s typewriter, and the cat kept jumping up in my lap, banging on the keys. I got rather angry and put him in another room, but then I couldn’t see. My eyes were all swollen shut, and my nose was running, and I said, “That’s the cat!” So the cat went to my sister’s girlfriend who lived a distance away it grew up to be a beautiful cat and it loved their home.

Q: So, what did your parents do for work?

Mrs. Rockett: My mother, when she was single, was an accountant in a store that is no longer in Boston. It was on Tremont Street; it was a very high-class store. She would walk from Charlestown to work.

Q: Lot of walking.

Mrs. Rockett: Well we were accustomed to it. I was working when I learned how to drive, and you just didn’t get use of a car and you certainly didn’t have money for a car. It was just a way of life that if you were going any place, you had public transportation. I worked in Cambridge, and I would take the public transportation everyday, but that was after I’d finished school. But one thing we did have that was fun: in the wintertime, when there was snow on the ground, and the snow would pack down on the street, the city of Boston had certain streets and neighborhoods that they would block off for coasting. Any street that was kind of a good hill, they did that. But the thing was, the nearest one to my house was right at the school that we went to, and that was about a half-mile from the house. So what we did was walk to school in the morning, leave school for lunch, go home, have your lunch, walk back to school.

Q: All in the snow?

Mrs. Rockett: Snow, rain, whatever. You were so accustomed to walking. Every place, you’d just walk, so we didn’t miss a car because we didn’t have the use of a car. But that was fun, the coasting. I enjoyed that.

Q: What about you Mr. Rockett? What did your parents do for a living?

Mr. Rockett: Where did they grow up?

Mrs. Rockett: No, what were there jobs?

Mr. Rockett: Oh, my father worked in Boston in a store that featured just linens and curtains. In those days it was appropriate, especially on Sundays, to have fine table-covers. But during the Depression the store fired most of the people, so he went out of that and opened a store in Brockton selling the same type of thing. But that didn’t fare well, so he sold that and we moved to Sharon. Although we had been in Sharon first, then to Brockton, then back to Sharon.

Q: And what’d he do in Sharon?

Mr. Rockett: In Sharon he started what we’d call a cleaning, tailoring business, and on weekends I would deliver for him. And he liked it because I didn’t mind going to the customers and telling the order’s money. And I would get three dollars a week for that. So with that three dollars, on Saturday night, I’d go to Lake Pural, that’s in Wrentham for dance, and I’d put a dollar’s worth of gas in the car, it cost me a dollar to get in, and I had a dollar to buy two beers.

Q: How far did a dollar of gas get you in the car?

Mrs. Rockett: Oh far.

Mr. Rockett: I remember driving for a week with a dollar.

Mrs. Rockett: We would pay nineteen or twenty cents at the oil fields over in east Boston.

Mr. Rockett: Yeah, I bought a new car for $900. New convertible, ’49.

Q: What about the hurricane of ’38? Do you guys remember what you were doing then?

Mr. Rockett: ’38? I graduated high school in ’39. So I was still in high school in Sharon.

Mrs. Rockett: We didn’t realize it was a hurricane. That was in September, so we had just come back from the cottage and school had started, and the street where the school was had poplar trees, and they are very vertical. And every ten feet there was one on one side and one on the other, all the way down the street. We walked into neighborhoods that had trees; we didn’t get the brunt of the wind, but every place there was trees they were downhill. The whole street was totally blocked with all the poplar trees. They all came down.

Mr. Rockett: I have a story. Lake Massapoag was about four miles, the circumference. This is a pretty big lake. So that particular day I was way out in a canoe, and the ocean waves, I said, “What is going on?” I said, “I’ll never get back to shore again with this stupid canoe!” Well I finally did, so I got it up on the ground, and I realized something was wrong, so I ran home. Well all the time I’m running home, these pine trees are keeling over like men! It was unbelievable! And some folk into the storm I think I made the best money, think it was seventy-five cents an hour to go around and saw, they didn’t have power saws when you did that. Sawed the trees and cleared the roads, but that was a nightmare.

Q: It sounds like an action movie.

Mr. Rockett: Yeah.

Mrs. Rockett: I think that we went to the cottage to see how that fared, and different buildings had floated out to sea.

Mr. Rockett: This is like being out in Nantucket Sound during this weather.

Mrs. Rockett: We really didn’t know. I can remember going outside the house with my sister and my father, and we were watching, we could see trees that were around our neighborhood but our neighborhood had been built by a contracted, and he didn’t put in any trees.

Mr. Rockett: We didn’t have TV going all day, every day telling you what to think and what to see. You learn on your own.

Mrs. Rockett: We were standing outside and we could see the debris going through the air, and we were saying, “What’s happening?”

Mr. Rockett: What’s going on?

Mrs. Rockett: Well hurricane was a new word we had because that was the first one we were really aware of, and that was totally different.

Mr. Rockett: There weren’t that many houses in Sharon that were damaged, even though things like that were falling all over the place.

Mrs. Rockett: The first tornado that was around here hit Worcester. I can remember sitting at the dinner table and looking out the window and seeing all this going through the sky, and I apparently said to my father, “What’s all that up there?” And he said, “Gee, I don’t know.” And I said, “Well gee that looks like roof shingles.” It was coming from Worcester, all that distance. We were lucky the wind had subsided by then, but it really was an eye opener because we had never experienced it before. It was different than the hurricane, and we were glad that that was the first and the last that was around here.

Q: So let’s turn to more political questions here. So when you were listening to the radio when you were little, did you ever remember hearing any of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “fireside chats?”

Mr. Rockett: Yes, people peaked around for that.

Mrs. Rockett: I know they were on, but I would find something else to do. I wasn’t into it yet.

Mr. Rockett: When Roosevelt came on, that was the advent of socialism because before people, if you didn’t have it, too bad. No one could come up and say, “Here’s some money, we’ll help you out.” When he came in, the government stepped in, and that was totally new. Of course it’s even more so now, but we won’t get into that.

Mrs. Rockett: But we would go to the movies and that was the way you got the news, the par-they news.

Mr. Rockett: Once a week we got the news.

Q: At the movies?

Mr. & Mrs. Rockett: Yup.

Mrs. Rockett: That was part; you got two programs, pictures, and in between you got the news.

Mr. Rockett: When I lived in Brockton, for ten cents you got two movies, a short subject, “Vaudeville”, and this thing that would come up everywhere, it’d be “The Perils of Pauline.” Every scene that you finished someone was going to fall off the cliff, next week they just fell to the ground. And you got all that for ten cents, and I got my ten cents from picking up bottles.

Mrs. Rockett: Yeah, we did too. We’d say, “Can we go to the movies?” And my mother would say, “Well you’ll have to turn in some bottles.” So we’d get our ten cents. We were never aware that he was paralyzed; Franklin Roosevelt was paralyzed, because they photographed him in any position. He was either standing or seated, it was not obvious.

Mr. Rockett: They did a good job of that.

Mrs. Rockett: I think that that was the biggest shock of his years as a president because people just didn’t know how ill he was. Well, by the middle of World War II, but that I can remember. He died in April, did he die in April? Do you remember? Oh, you weren’t around. One of our neighbors came running and he was yelling at me, and I didn’t know what he was saying, and finally it got through to me, “Roosevelt’s dead!” And then all the neighbors started coming out and talking about it. Nowadays, nothing is private.

Q: Yeah, the press was really nice about his illness.

Mrs. Rockett: Well, in those days, I won’t say you minded your own business, but you weren’t aware of every little nuance in everybody’s life. Like now, look at the way the paparazzi goes around to all the movie stars. That didn’t happen, and movie stars were having babies out of wedlock then and you never knew it. If the movie star wanted to have the child, and the child was probably two years old before you knew that she had this child. But you didn’t know if it was an adopted child, so that’s the way they passed it off, and she wasn’t married.

Q: What about his wife Eleanor?

Mrs. Rockett: I don’t know if she was as popular until after he died.

Mr. Rockett: No, she was subservient to him. Although, everyone knew she was quite knowledgeable, but she stayed in her place, you might say. After he died, then all her abilities and writing all came to the forefront.

Mrs. Rockett: And then she had a column in the newspaper, and she was going politically around the country and to other countries.

Mr. Rockett: Now women weren’t put in the political arena at all. They were just shunted to the side.

Mrs. Rockett: They didn’t even have the right to vote until afterwards.

Mr. Rockett: See how lucky you are?

Q: Yeah.

Q: So do you remember any of FDR’s programs in the New Deal, such as the CCC or the WPA?

Mr. Rockett: No.

Mrs. Rockett: I think the street where I lived was done by WPA, and I think my brother-in-law, my sister’s husband, was in the CCC because that kept them occupied.

Mr. Rockett: In Brockton they made a park, nice park, put in brickwork and everything like that, dug a swimming pool. And then the CCC, the Civilian Conservation Corps, they did a lot of work in the forests, to trim out trees and things like that.

Q: Let’s see, did your parents think that the New Deal was a good program?

Mr. Rockett: They didn’t get involved in it.

Mrs. Rockett: Well I know my parents would discuss it, but I didn’t absorb it because I wasn’t interested in that. I guess I was just probably; I’m trying to think how old I would have been. I think I was just starting high school because World War II started just before I graduated basically.

Mr. Rockett: People then were really independent. For example, you’d think to buy something; there was no such thing as credit, no such thing as a credit card. When you saved up enough money, then you’d buy it, but until that, you just did without. They didn’t lose any sleep over it, that’s the way they lived.

Mrs. Rockett: The advertising wasn’t geared out to every moment of your day. Now you get it in the mail; you get it in the newspaper; you get it on TV.

Mr. Rockett: Everything you do, there’s advertising confronting you.

Mrs. Rockett: And they don’t show you one ad in a program on TV. It’s ten minutes of ads. We weren’t bombarded like that. They make you feel like you’re missing out on something, like when you go to the doctor, you don’t even know what the medication is called.

Mr. Rockett: Most of these “ask your doctor” medicines will kill you anyhow, so stay away from them! It’s only beneficial to pharmaceutical companies, they could care less about you.

Q: So, do you remember anything in the thirties about what was going on in Europe at the time? Like Hitler’s rise in Germany?

Mr. Rockett: Well there was a Catholic school next to me, and the chaplain had been to Japan two or three times. And we were just amazed when he’d come back and say how much more advanced that country was at certain things than we were. Now I’ll never forget, I went to a movie tunnel for the news once, and it showed in Java this one submarine, and that was supposed to defend them against anyone that tried to commandeer their oil. One submarine, it was a joke, but we all looked at that and said, “Wow, they’ve got a submarine!” And that’s how we got news. And then I was aware of the Japanese moving into China; I was aware of Hitler starting out. I was aware of Neville Chamberlain making a national mistake; instead he comes back and solves the problem. The next day the war started. We got that through the news, and when I moved in the defense plant in Connecticut, this is a little later, in the early ‘40s; we were making planes for aircraft carriers. And we said one day, “Well you don’t need aircraft carriers around here in the East. They’d have to be in the West Coast, the Pacific, so why didn’t we need aircraft carriers over there?” We didn’t take it to the next step as to why. Then when I went to a school called New England Aircraft School, my buddy and I used to say, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could go to Pensacola and learn to fly, and then assigned to Pearl Harbor. Wouldn’t that be great, with the white uniforms?”

Mrs. Rockett: Of course everything changed after World War II as far as transportation and all the airplanes and things, so you only went as far as your car would take you, so you didn’t travel that much. Families didn’t move, now we have a son that’s in California and one’s in New Hampshire. Well that was unheard of in those days. It’s just totally different, and I see things differently than he does because of the difference in our age. I’m four years younger, so I was a little behind the times on catching up with all of this information, and I don’t think girls or women got involved the way they do now. And you didn’t hear about it, it wasn’t something that you thought.

Mr. Rockett: It all changed with the war, because then, for the first time, it got us out of the Depression, so we needed a war to change things. A lot of countries have done that throughout history: get the people busy, get their minds off of how terrible things are, start a war, and that gets everything going, and that’s what happened here. Now when I got the job in Connecticut, I made fifty-five dollars a week, and I got some overtime. I couldn’t believe that because my earlier job before that was twenty dollars a week, and the one before that was eleven. So I was moving upscale, and it was all because of the war.

Mrs. Rockett: I started at twenty five.

Mr. Rockett: Yeah, well you were a skilled person, it was just the labor

Q: So families must have been much closer together then if they all lived together.

Mrs. Rockett: Yes. I think my mother and her sisters, well she had a cousin that she called a sister, and a week didn’t go by that they talked for hours on the phone. My mother’s friend’s sister, she was the one who worked, she would call two or three times a week. And it would be at night because she wouldn’t use the telephone at work.

Mr. Rockett: Tell her about the telephone system, the party line.

Mrs. Rockett: We didn’t have too much of that, you did.

Mr. Rockett: You’d pick up the phone, and someone else could be on it, two people paying for that one line. Or it could be three people paying for that one line. So if someone else is using it, you just come back later on if you can’t wait your turn. We got a dial tone, that was something new, to get a dial.

Mrs. Rockett: Well, I didn’t think we were on a party line when we very first moved in Dorchester. I remember my mother was so pleased when she got a private line.

Mr. Rockett: That was a big deal to get a private line.

Q: Yeah that must have been.

Q: So going back to your high school experience, just what was it like? How much work did you guys have to do in school?

Mrs. Rockett: Well, I imagine you’re still kind of channeled. I was told that I would never get to college because we just couldn’t afford it, so I took a commercial course. I read someplace, or either they told us, that if you do merchandising you would go out on a job, so I guess it was my junior year, I was in merchandising. It was December and there was a W.T. Grant store on Washington St. in Boston, and I was folding socks. My mother said that I was folding them in my sleep. She went in one night, and there I was my hands were going. But the big thing I remember about it, I don’t remember how much I got, I don’t remember where I ate my lunch or anything about the job other than the folding socks and they played music all day long. And that was when “Elmer’s Tomb” came out. I heard that until I was ready to scream; I was so glad when the month ended, so that I could go back to school. You were channeled. If you took a commercial course, you would get up and go into the office-work. We even had different schools. In other words, there was one school, one high school, in Boston was home ec. If you wanted to go in baking or something like that, or sewing, and another one was, there was one for boys that they would have woodworking.

Mr. Rockett: Like a trade-school.

Mrs. Rockett: So if you got stuck in there, unless you went to some training school afterwards, you…

Mr. Rockett: Well, schooling then was more demanding than it is today because you had to be able to multiply in your head. You didn’t get a computer; you had to learn to spell; you had to write; you would check for grammar, if it wasn’t right they’d throw it back at you. So I can remember interviewing kids from college, and I’d have them take out a piece of paper and write down anything you want and go through it, and they had no idea what they were doing to convey a thought. Logical fashion, punctuation, grammatic style, they were dead-up between the ears, but they call themselves college graduates. We couldn’t get through high school or even grammar school without being able to do that, forget about college.

Mrs. Rockett: I remember I was an all “A” student…

Mr. Rockett: I remember I was “A” for “Awful.”

Mrs. Rockett: Then in junior high school, which was 7th, 8th, and 9th grade, we didn’t call it middle school, it was junior high school. The first year I was in a mixed class, and then the next year I was in an all girl’s class, and the last year it was a mixed class again. I think half-way through it would turn around. You’d have the two classes of girls and one mixed class half-way through the year. It was very inconvenient, but I went to an all girl’s high school.

Mr. Rockett: I want to bring up another thing I don’t want to miss on. If, in that time, they ever heard the expression, “Time-out,” they would laugh themselves silly. The adult gets down to a two-year-old kid, and gets in this adult conversation. He doesn’t know any idea in the world what they’re talking about. In our days, when the parents said “No,” or “Don’t do it,” that was it. That ended it. They didn’t beg you to do anything, that was it, and you didn’t bellyache or you’d get a swat, but today, parents practically get down on their knees, “Oh pretty please?” That didn’t exist.

Mrs. Rockett: Well I think today because many of the parents or mothers work, that they feel that they’ve got to be very nice to the child when they are around because they want to be loved. And discipline is lacking. It horrifies me to hear how many special education students are in Wayland. I think a lot of it is a natural ingrown action and these mothers who see the child only at night or when they are not on their best behavior and during the weekend that they panic and there is something wrong with this child

Mr. Rockett: I take quality time as doing the kid a favor. In our lifetime, all day everyday was quality time.

Mrs. Rockett: Plus the fact there was discipline. You didn’t talk back you didn’t expect it. If a police man spoke to you respected him, you did what you were told, in the same way with the teachers. You didn’t act up in class and if you did you were out of the class.

Mr. Rockett: We didn’t have liquor or drugs and if we did we didn’t have the money to purchase it. I didn’t know the word marijuana until I was in the service…

Mrs. Rockett: I don’t think any of the fellas I dated smoked. I didn’t smoke. One of my girlfriends smoked and I can remember she came to my house one night, we were going to go out together, and she sat in the big arm chair and she was smoking her cigarette and the next day my mother said, “Maybe you should take up smoking, Dorothy looked so glamorous”. (Laughter) I said I don’t like the taste in my mouth.

Mr. Rockett: Well that’s the way movies handled it. They had a butt in one hand and a drink in the other. That was supposed to be stylish.

Mrs. Rockett: And drinking I did not know. We didn’t have alcohol in the house because my father didn’t drink. My mother had a bottle that she hid in the closet that was for medicinal purposes.

Mr. Rockett: My mother used to hide candy in the closet but I knew how to pick the lock. (Laughter)

Mrs. Rockett: I guess we were just trusted more because my father would come home candy from Charlestown. Candies that maybe the chocolate didn’t totally cover the filling maybe you know the design on the top would tell you what’s inside. Well they called those seconds. And he would come home with a box very high just full of chocolates and I think he paid fifty cents for it. So my mother would hide it. But we’d always find it.

Mr. Rockett: Another thing, medical care. You know when you saw your doctor? On your death bed! You never went to a doctor.

Q: You didn’t have check-ups or anything?

Mr. Rockett: No that didn’t exist.

Mrs. Rockett: And you didn’t get vaccines for this and vaccines for that.

Mr. Rockett: Now you are getting too many vaccines

Mrs. Rockett: I had scarlet fever and I had to be in bed and my sister and I shared the room and the doctor said “don’t let her near her sister”. I don’t know where she slept but-

Mr. Rockett: On the floor. (Laughter)

Mrs. Rockett: she didn’t sleep in our room and my mother used that bed and my mother would say “well take this up to grace”. And if it wasn’t food, if it was something to read or I don’t know what else, it could have been an article of clothing, she’d throw it at me. (Laughter) Just when you were sick you went to the doctor or the doctor came to the house.

Mr. Rockett: You didn’t ask where our parents came from…

Q: You kind of mentioned how kids are different today than back then, but what else was there?

Mrs. Rockett: Well it was totally different bringing up children in those days. You didn’t ask for everything you saw. There weren’t the funds for it. And if your parents said this was going to happen, you didn’t try to talk them into a different thought. You just kept your mouth shut.

Mr. Rockett: It was more on the surface respect which doesn’t exist today. You can call me wrong, but as I see it.

Mrs. Rockett: Well he is talking about little kids

Mr. Rockett: No the big ones too.

Mrs. Rockett: Well yes they like to razz you and things like that but because I’m still doing the driving he drives when I’m not in the car.

Mr. Rockett: I use the side walks quite a bit! (Laughter) Get out of my way! . . .

Mrs. Rockett: I do the driving a lot of times and I get the feeling a lot of times that the younger people have no patience because they think I am a terrible driver. I am not. I go by the book. And when I learned how to drive you stopped at a stop sign you didn’t roll through it. When you stopped at a light you didn’t take a left turn, now you can take the right turn. But also it’s just so different.

Mr. Rockett: You people came through life with seatbelts but every day you hear about kids in accidents being thrown out cars. Seat belts aren’t artificial. Didn’t you get into the habit of it? I am not addressing you personally but you hear about it all the time, people getting thrown out of cars for not using seat belts. . .You still have some more questions to ask?

Q: So what lessons do you think we can learn today from the times of the 1930’s?

Mrs. Rockett: I think you can learn how to manage money better and not have everything that everybody says you should have in other words advertising or even what you see on TV its “oh they’ve got that? I have to have it”. You don’t have to have everything.

Mr. Rockett: And don’t follow and slave by being politically correct. That’s just someone else doing your thinking for you. Don’t let your head be a hat rack. Use your own thought process. Be independent.

Mrs. Rockett: I think the biggest thing is look at the way people line up for a game. And it’s all advertising. I think you are being brainwashed that you have to have everything. That is why there are such big houses because everybody has everything. I shared a bedroom, he shared a bedroom, everybody has to have their own bedroom and their own TV and their own laptop, and their own this and their own that. We can see it in our own family because we have two grandchildren 13 and 8 and they each have their own TV in their bedroom…

Mr. Rockett: You know I haven’t used a cell phone yet. That drives me up a wall. What was communication so important they can’t leave the house without beating their gums up and down? Can’t you wait to get home to pose the question? What’s it all about? Someone leaves the house, they’re on the phone! Couldn’t you use the phone before you left the house?

Mrs. Rockett: But what is so important that you have to be on the phone all the time. I mean I don’t call people for weeks at a time.

Mr. Rockett: Do you feel lonely? Do you need to have some communication? Is there something missing in your life that you have to be yapping all the time?

Q: I think we were just given it from the start so we’re so used to it. It’s right there. The phone is sitting right there, if you have to tell someone something you just…

Mrs. Rockett: I think that people are in such a rush to do so much that they don’t have enough time to be on time so they are dashing here and there.

Mr. Rockett: You have it all but you really don’t appreciate it. You have too much. I say you have things you have everything.

Mrs. Rockett: I am still wearing clothes that I bought maybe 20 years ago…When we got married he said, “We’re going to live by a budget”. We still do. Everything that we spend well not everything but we have a book and the pages marked off and we did this when the children were young. And it wasn’t living the way we were brought up it was just what we decided to do. We were going to live within the amount of money that we had. And so when I would go out for clothing, I would put down what I bought and the kids would say, “Well I need this or that”…

Q: What do you think about credit cards and everyone in debt?

Mr. Rockett: I pay as soon as the bill comes and I’ve never paid a penny interest.

Mrs. Rockett: We didn’t encourage our sons to take them out in school. When they were home and in high school if they wanted a baseball glove or a bike, wed say you save half and we’ll pay half. And that way we thought we were teaching them how to handle money. (Laughter)

Mr. Rockett: It was the idea if they had the bike and just threw it down somewhere they would be more careful with it because it was their property…Let me throw a question at you. What are you going to do when the gasoline runs out and you get 3 gallons a week to drive? What are you going to do when there are no jobs around? Are you going to go to hotel, work for someone who owns the hotel? Just realize that in probably twenty, thirty years, you’re going to be the minority. All these other races which are propagating like mad are going to be taking over…Things change. At one time we controlled the world, now it’s changing, one time Portugal, Germany, Russia, things change. We’ll just be down at the low end of the totem pole and you have to go on with it. It won’t be the good life like today. I hate to say that…all these things are happening and the people who are supposedly leading us, couldn’t lead kids to free ice cream, are not making any decisions. They aren’t doing anything! . . .

Mrs. Rockett: I think that there should be more publicity about the possibility of using the sun because we, back in the seventies, when there was a shortage of gasoline, started to investigate solar power because we lived in a ranch house…

Mr. Rockett: Let me give you this impact message. Years ago, when President Kennedy was around and the Russians put the first man on the moon, he said “we’re going to take all meaningful resources and apply them to this project to emulate what the Russian’s did”. That is what we should have done twenty or thirty years ago on the oil to get something to replace it. And Al Gore just isn’t the answer. If you’re going to take all the food crops and deplete the soil, you have to remember in the thirties they did that and it ended up as a dustbowl. A friend of mine in Arizona used to know a German scientist and he had developed a car that would run on hydrogen. Way back then! Of course we’ve done nothing. We always felt that when the car company found out a way to develop a better car or get better mileage they’d buy it up and put it in the closet. Well it’s too late now. Even if we found out something today it would take at least a decade before it would get implemented. But once again, we’re staring into space…

Mr. Rockett: As difficult our life was, you face the possibility of one much more difficult if you don’t resolve some of these major problems. We just named a couple but I could name a dozen we just don’t have the time. We will let the professor do that. (Laughter)

Mrs. Rockett: I feel that you girls should feel that you are able to do anything because you can if you stick to it-

Mr. Rockett: We wish you well

Mrs. Rockett: -and have a concept of something you will follow through on it because we weren’t encouraged to do that. We were encouraged to get a husband to support us.

Mr. Rockett: She is one of the lucky ones. (Laughter)

Mr. Delaney: Well thank you very much for coming in you guys.

Mr. Rockett: Pull the plug!