- Anne Hale: The Case of the Communist Teacher

- Baseball: A Way of Life

- Chuck Taylor Hightops: WHS Basketball

- The Baby Boom Explodes

- "Mrs. Everywoman"

- Warriors Football

- Nightlife Up in Smoke: The Mansion Inn

- Not-So-Fast-Times at Wayland High

- The Sirens of Wayland: The Police Department

- Cold War Wayland: Nike Missile Site & Raytheon

- Keeping Up wit the Joneses: Consumerism in the Town Crier

- A Sense of Community: The Strawberry Festival

- Newsletters to Those at War: The Bugle and the Jeep

- A Quieter Life: Coming Home from World War II

- Duty Calls: Veterans of the Korean War

- A Simpler Time: Growing Up in Wayland

- Old Meets New: Dudley Pond

- Flash Movie

The "Red Menace": Anne Hale, Communist Teacher

2004 Local Historians: Jen Huang and Kathryn Paul

The year was 1954, and Wayland was experiencing a huge growth in population. Young families and young couples looking to start a family poured in. It was a time when the long-time residents had to part with feelings of ownership of their small rural town. The new families got more than just the expensive schools they wanted; their influence brought about a tight-knit community. It was a time of carpooling and babysitting; of light gossip amongst neighbors who shared a similar point of view. It could have been any growing town in the northeast, maybe even the country. Wayland was a town of thoughtful and rational people, but it was by no means immune to the anti-Red hysteria going on nationwide. Says Mrs. Edith Stokey, wife of Town Counsel Roger Stokey, a few overly-vigilant residents got caught up in the hunt:

"One of the stories was that there was a regular meeting of a communist cell in Wayland. The evidence was that every Thursday night the same group of cars convened at the same house. The gentlemen who reported it took down the plate numbers and reported them to the FBI. The truth of the matter was that this was a ladies' bridge club. . . "

". . . we too [Mr. and Mrs. Stokey] were reported. Our sin was that we had

taken our shutters off our house to paint the house and had not put them

back on. This was viewed as highly suspicious because Ned Goodell who lived

near us had done the same thing. He was generally believed to have been a

member of a former member of the Communist party. So if we took our

shutters off, that must be signal. . . "

". . . we too [Mr. and Mrs. Stokey] were reported. Our sin was that we had

taken our shutters off our house to paint the house and had not put them

back on. This was viewed as highly suspicious because Ned Goodell who lived

near us had done the same thing. He was generally believed to have been a

member of a former member of the Communist party. So if we took our

shutters off, that must be signal. . . "

This was an age when North Korean communists shooting at UN troops as they attempted to take the entire Korean peninsula. This was when the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were sentenced to death on charges of divulging coveted military secrets to the Soviet Union. "Duck and Cover" drills were regular occurences in public schools in case of a nuclear attack. During this period of hostility towards communism, Massachusetts teachers were required to take the oath (up until 1949):

"I do solemnly swear that I will uphold the Constitution of the United States and of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and that I will oppose the overthrow of the government of the United States of America or this Commonwealth by force or violence or by any illegal or unconstitutional method."

This is the key to Miss Anne Hale's history in Wayland, the story of a

former communist dismissed from her job as a second grade public school

teacher. Known to the FBI as a rather benign member of the Communist Party,

Miss Hale nevertheless lost her job due to her political affiliation. Her

files describe her as a quiet lady without many friends who'd spend most of

her time with her pet dogs and, on occasion, "a colored lady who appeared

to be advanced educationally. . .whom she believed to be a doctor or a

teacher." Very suspicious.

This is the key to Miss Anne Hale's history in Wayland, the story of a

former communist dismissed from her job as a second grade public school

teacher. Known to the FBI as a rather benign member of the Communist Party,

Miss Hale nevertheless lost her job due to her political affiliation. Her

files describe her as a quiet lady without many friends who'd spend most of

her time with her pet dogs and, on occasion, "a colored lady who appeared

to be advanced educationally. . .whom she believed to be a doctor or a

teacher." Very suspicious.

On April 23 Miss Hale stood before the Wayland School Committee in sworn

testimony. Her membership to the Communist Party, which ended two years

after accepting a job at Wayland, had been discovered. In this private

meeting she openly acknowledged her involvement and answered the Committee's

questions surrounding her communist activities. Her statements were

recorded. They would later serve as the basis of the trial (most of the

following are reiterations of her testimony found in her own letters to the

Town Crier in June 1954):

On April 23 Miss Hale stood before the Wayland School Committee in sworn

testimony. Her membership to the Communist Party, which ended two years

after accepting a job at Wayland, had been discovered. In this private

meeting she openly acknowledged her involvement and answered the Committee's

questions surrounding her communist activities. Her statements were

recorded. They would later serve as the basis of the trial (most of the

following are reiterations of her testimony found in her own letters to the

Town Crier in June 1954):

- I should like to repeat what I have already said I have not been a member of the Communist Party since the end of 1950 nor have I been active in its behalf since that time.

- The Communist Party was a political organization dedicated by lawful means through majority action to establish Socialism in this country.

- I have never advocated, nor heard any one else connected with the Communist Party at any time advocate sabotage, espionage, sedition or the violent overthrow of the government.

- When I came to Wayland to teach in 1948, I considered carefully the meaning of the teachers oath. I could certainly say with perfect truth that I would do my best to uphold the Federal and State Constitutions. That I wished to see them amended was not contrary to such an oath. The constitutions themselves contain provisions for amendment, of course. My father was a delegate to the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention that was held about 1910.

- She claimed that she was unaware of the act that declared it illegal for the Commonwealth to hire a member of a subversive organization.

A month later, she was given a formal write-up of the charges against her as

well as a notification that a vote on her dismissal would be held in June.

The charges against her, as reprinted in the

Town Crier, are as follows:

A month later, she was given a formal write-up of the charges against her as

well as a notification that a vote on her dismissal would be held in June.

The charges against her, as reprinted in the

Town Crier, are as follows:

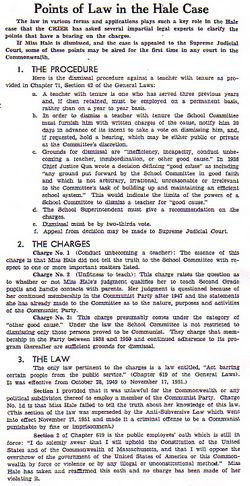

- (Conduct unbecoming a teacher): The essence of this charge is that Miss Hale did not tell the truth to the School Committee with respect to one or more important matters listed.

- (Unfitness to teach): This charge raises the question as to whether or not Miss Hale's judgment qualifies her to teach Second Grade pupils and handle contacts with parents. Her judgment is questioned because of her continued membership in the Communist Party after 1947 and the statements she has already made to the Committee as to the nature, purposes, and activities of the Communist Party.

- This charge presumably comes under the category of other good cause. Under the law the School Committee is not restricted to dismissing only those persons proved to be Communist. They charge that membership in the Party between 1938 and 1950 and continued adherence to its program thereafter are sufficient grounds for dismissal.

Not willing to let the matter be settled in secrecy, she requested a public

trial. She wanted to show that her idea for a better world had no influence

on her teaching. To dispel any mystery about the charges against her she

published numerous letters in the Wayland Town Crier. These included a

letter to her students, the history of her communist period, and

reiterations of her statements from April 23rd.

Not willing to let the matter be settled in secrecy, she requested a public

trial. She wanted to show that her idea for a better world had no influence

on her teaching. To dispel any mystery about the charges against her she

published numerous letters in the Wayland Town Crier. These included a

letter to her students, the history of her communist period, and

reiterations of her statements from April 23rd.

My Father, when I asked him to define a successful person, gave his definition as one who had helped the broadest group of people to the utmost of his ability. This has been my goal for success in life ever since.She speaks of her frustration with a private school where she taught and her inability to contribute to anything positive. She speaks of being impressed with the sincerity of the Communists and her apprehension with joining them because of the notion that they advocated violence.

For a long time I held back, because I was told by others that they believed in force and violence. After some study and investigation of this I found that they taught that socialism could come only when the majority were ready for it, and chose a socialist government. Their other objectives being the same as mine: to improve conditions for the underprivileged, by basic changes when the time came, but until then by working for jobs, peace, democracy, better housing, better schools, and so forth, I felt there was no further reason for hesitation, and I joined the Communist Party in June, 1938.Roger Stokey, as the Town Counsel, had the unpleasant task of prosecuting Miss Hale. Stokey did not refuse the job knowing the trial could potentially be handled very badly, and knowing he would do his best to conduct the case fairly. The political climate had made this a very delicate operation. The McCarthy-Army show trials coincided with the hearings and could be seen by anyone with a TV. (The trials were joked about on the first night of the hearing; called Wayland's "competition in Washington" by the Crier.) This was not the peak in McCarthy's popularity; it was actually the beginning of his rapid downfall.

It did however play on the curiosity of the citizens. It was that curiosity that, on the first night, packed 700 spectators into the High School gym (now the Town Building). What they witnessed, however, was the exact opposite of the reckless brutalizing of a witness from a demagogue foaming at the mouth. Hale supporters would commend Stokey for, as Mr. Waldron, a member of the School Committee who voted against dismissal,stated "Proceeding carefully, conscientiously, and intelligently." The hearing included a short list of witnesses called to the stand, among them teachers from the school and an FBI agent. Mrs. Edith Stokey says the hearings were intentionally dulled down to curb public interest. By the third hearing attendance had tapered significantly.

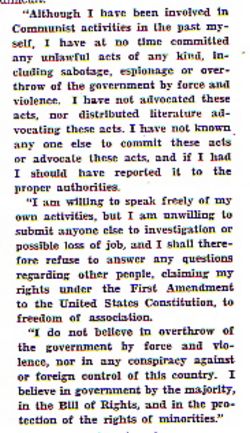

Another source of dying interest was the defiance of Anne Hale. On April 23rd, most would have denounced everything they formerly stood for, called their participation a misguided experiment. Miss Hale never cited disillusionment to explain her departure from Communism. She cited a preoccupation with other more pressing organizations. Many would have accepted a private firing and packed their bags without question. The way she conducted herself during the public trials caught everyone off guard. When asked a question regarding her knowledge of the communist agenda or activities during that period she simply refused to answer. One night a reporter counted 39 refused questions. This is the Crier's account of the first night:

"Miss Hale reads a two page statement, the gist of which is:

- She told the school committee on April 23 of her political beliefs on a voluntary basis

- She believes this is a private matter and when asked under compulsion she is not obligated to answer.

- She had answered the committee questions previously because she wanted it understood that she held unpopular views and felt she had a right to hold them.

- She admits the right of the school committee to question her on matters pertaining to any proof they might offer that she was not sufficiently prepared to teach or that she lacked perception and judgment in dealing with children or parents.

- The constitutions of the United Sates and Commonwealth forbid such inquiry as does Chapter 71, Section 29 of the General Law.

The Committee, apparently taken by surprise by this development, recesses."

As her responses became scarce so did her sympathizers. The League of Women Voters wrote a Letter to the Editor distancing themselves from Miss Hale. One group that stood firmly behind her was the Unitarian Church. Because the attendants were predominantly young liberals and Miss Hale was never excommunicated, the Unitarian Church was believed to be a hot bed of communism. Reverend Raymond Manker reflects on the atmosphere of the 50s in a 2002 sermon:

On going to Wayland, Massachusetts, in 1950, I was only 25 years old, and I did not have the wisdom of years that Arthur had earned. Soon, at the high point of the "red scare" of Senator Joseph McCarthy, I was in trouble for openly speaking my mind. Several in the congregation were incensed over my sermons, and demanded that the Standing Committee fire me. Fortunately, the congregational vote retained me, and a goodly number of previously uncommitted liberals in the community, on seeing the congregation support me, decided to join the church and give added support. It was then that the F.B.I. started to build its file on me. I supported Anne Hale, a member of my congregation, a popular, well-loved school teacher, who was being hounded and finally fired by the school board for having once been a communist, and who refused to beg for pardon. It hit the front page of the Boston newspapers, and we received hate mail and terrible telephone calls. But my great congregation stood firm.There were three ways Stokey could have had her dismissed. The first: under the charge of conduct unbecoming of a teacher. If any of her statements from the sworn testimony on April 23rd were found to be outright lies. Without Miss Hale's cooperation, this proved to be difficult. The prosecutors were forced to lean on a second route: the charge of unfitness to teach. They had to prove that there was a widespread acceptance among the communists of the use of force and that there was a widespread knowledge of the anticommunist regulations on public schools at the time she signed her applications. Accomplishing this would make her look like a sheltered innocent, blinded idealist, or ignorant fool (the dissenting Committee member on what was trying to be shown.) The third charge could be substantiated if the Committee finds her adherence to the communist doctrine makes her unsuitable as a teacher. It became a trial grounded in judgments as apposed to legal points. The Committee overrules Miss Hale's lawyers repeated objections saying that, as a hearing and not a trial, we are not bound strictly to the rules of evidence. When justice crosses over into this territory even the most well handled examination can become insulting. It was certainly no spectacle, but moments of drama did find their way into the proceedings, as reported by the Crier:

Stokey wants her to state her grounds [for refusing to answer]. Mr. Allen [her lawyer] asserts she is not legally qualified to answer such a technical question, Mr. Stokey says, If Miss Hale can't tell under what act she claims immunity she hasn't the judgment to be a school teacher. (Applause). Mr. Allen: I regard that as a most ungracious remark. I hope they did not think they were coming here for a lynching. Both remarks are stricken from the record.The decision was reached 2-1 and called for the dismissal of Anne Hale. Both the majority and minority opinion spoke at length of their frustration with Miss Hale. The majority made clear their contempt for her communist affiliations:

;We would like to point out at this time that we are fully aware of the protection given by General Laws, Chapter 71 Section 30 to political opinions and affiliations. We do not believe that this statute protects affiliations with a conspiracy which masquerades as a political party. We consider the Communist Party to be such a conspiracy. Therefore, questions may properly be asked regarding affiliations with it. Despite our views of Chapter 71, section 39, in reaching the conclusions stated below we have not taken into consideration Miss Hale's refusal to answer questions.It is interesting to note the difference between this statement and Miss Hale's belief in the principle that no one should lose his job on account of his political convictions. The majority came to the conclusion that, regarding two of the counts under the 1st charge, she was in fact lying.

We cannot believe that Miss Hale, in her twelve years of activity in the Communist Party did not learn this doctrine, or hear it advocated, or know of the distribution of literature advocating it. Her experience was too long, her activities too varied, her acquaintances too wide spread, her study of doctrine too extensive, to permit us to reach such a conclusion. We conclude that she did not tell the truth on April 23, that she did so in order to defend the Communist Party, that charge 1 (c) is substantiated, and that she should therefore be dismissed.

Regard the charge of unfitness to teach they said:

Without reviewing the evidence at this time, we believe it sufficient to say that even the most charitable view of this case shows that Miss Hale has demonstrated an almost complete lack of perception, understanding and judgment.They also justify dismissal under the charge that following communist doctrine impairs the ability to teach. They speak of the impressionability of second grade, their inability to judge and reject ideas.

The dissenting voice can be heard as pained and perplexed. In the writing of Walter Waldron one can see a tremendous struggle. On one side he was suspicious of the testimony Miss Hale gave on April 23rd and he has doubts about her honesty. He found her political convictions abhorrent and recognized that the publicity had done irreparable damage to her reputation with the parents. He felt that he had no reason to believe that her opinions of the Communist doctrine had changed in the least since 1950. His colleagues wrote of substantiated evidence with steadfast certainty. He wrote of the possibility that his decision is less realistic than the majority's. The dilemma was complicated by the impossibility of pulling facts from a silent response. His dissent began with a lengthy introduction in which he lamented her refusal of the questions asked. He admitted that if he were allowed to hold her silence against her he would not have differed with his colleagues. But the fact that her guilt was not proven would not allow Mr. Waldron to vote for dismissal.

I realize too that as a member of the School Committee I have a duty to do all I can to promote the interests of our School Department. However, whereas here Miss Hale's record as a teacher has been good, I believe that I may have a higher duty- particularly as a lawyer trained to the legal significance of the principles and traditions embodied in the Declaration of Rights of our Massachusetts Constitution and the Bill of Rights of our Federal Constitution. And that duty is to uphold the right of all citizens including teachers to freedom of belief and lawful association in their private lives.He called this one of the most difficult decisions in his life. This was not a popular response; he was never reelected.

Public discussion of Anne Hale dissipated quickly after her dismissal. For Wayland residents life went on, but Miss Hale had a harder time moving forward. She was a lonely woman and never got married. She dabbled in other professions, but again, employment was difficult for a known subversive. She tried to start a small summer program in Wayland for kids from Boston. She got a job cleaning cages, but was fired when her communist past resurfaced. Near the end of her life she taught children with brain damage. She was never allowed to again contribute to the town of Wayland; she never got back to the years which she said were the "happiest and most rewarding years of my life so far."

Transcript of interview of Joyce Wilson

conducted by Felipe Sanchez and Will Barnett on May 24th, 2005

Wilson: So what do you want to know?

Wilson: The fact I am giving you these pages is because they devote one-two sentences to the school committee members who voted on Anne Hale's dismissal who held the hearing devoted only two sentences in their report to the town of that event.

Sanchez: It's also kind of interesting that like we read the uh newspapers from around that time period the '54 Wayland Town Crier...

Barnett: Yeah and there was very little written about her.

Sanchez: There was this whole fantastic entire paper and then the next month nothing; no editorial...

Wilson: Wait, yes, what I guess I'm trying to get across to you is that though it seemed like earth shattering stuff it got very little notice. The state of Massachusetts legislature had a communists committee selected legislatures from the state met with FBI people and all sorts of people and then declared that there was all these 80 some communists in the state of Massachusetts. Communism was a real dirty word because McCarthy was, Sen. McCarthy was in control of the airwaves and he was having these hearing on all these horrible communists people who were absolutely dismantling Hollywood and everything else because they were giving all of us lies and....

Sanchez: Uh, yeah I'm sure that they...

Wilson: And there was hysteria in some parts of the country but Massachusetts being Massachusetts treated this very lightly, although there were some people in town who thought there was a communist behind every tree.

Barnett: Yeah, we actually read something at the historical society were there is this story of people who took there shutters down and um some neighbor told the FBI because um two neighbors and uh they thought it some weird signal the commies had.

Wilson: Some kind of signal plus the fact that all of these three Wayland people who were named to be communists lived in red houses...

Barnett & Sanchez: [Laughter]

Barnett: Are you serious?!?

Wilson: [inaudible], Ned Gavell in a red house, and Elizabeth Raymond lived in a red house and they were all just painted red they weren't red because of any reason, they were just old barn red that everyone else painted there houses. But since all, but then everybody else who lived in a red house people began to say "Maybe the Waldrons...oh maybe these people, oh maybe the Waldrons!" so that, it was so silly! But not everybody did that, obviously. [coughs] And you know enough to know that Anne Hale was a respected teacher...

Sanchez: Yeah

Wilson: She was teaching second grade, well, that caused a lot of people to say what could she possibly be doing that bother people in the second grade? If she had been a high school teacher, there might have been more concern, if she been teaching social studies there might have been reason to say "y'know she's trying to teach the kids something that is wrong"

Sanchez: Teaching them socialist studies

Barnett: Right, socialist studies!

Wilson: That, that...there was enough concern so that people were sort of taking sides and the fact that little Wayland, although growing, had three named communists by the state commission...made everybody a little more aware of what was going on. What Anne Hale did that was different was that she demanded a public hearing on being fired. The reason that she was being considered for being fired was not because she had been a communist but because she had signed her application had saying that she never been affiliated with the communist party which was part of a legal thing that you had when applying for a job, you had to say whether or not you had ever been a part of any subversive group. It was so shortly after the war...

Sanchez: The Korean War...

Wilson: World War II, and the Russians getting the atom bomb that people got itchy.

Barnett: Yeah, um, so that was sorta the, ah, climate of the town, it was sorta, ah, anti-Red and anti-subversive but there wasn't this hysteria.

Wilson: It wasn't universal in the town tend the fact that she had been a good teacher and wasn't affecting anyone made an awful lot of people angry at the idea that she had to come up for dismissal. There was little understanding of the reason being that she had signed her name to statement that wasn't true and she did admit that she had indeed been a member of the communist party, and she did admit that she joined organization too...uh...to proselytize her thinking. But by the time she was teaching school out here, she had lost contact with the cell that she had been involved with. So she was really harmless. [laughs] I'm using that term lightly, harmless is what people would've said she wasn't really vindictive she wasn't trying to turn people into...uh...

Sanchez: I'm sure people were a little bit, y'know, at odds with the fact that she is teaching such impressionable young kids opposed to...

Wilson: Well there was that angle too, even though it was probably, most people would have thought if she was teaching high school students it would have been more scary than teaching second graders, but there were people who just like you said, thought that they are so impressionable at that age she will surely corrupt them. Um...she wasn't a very aggressive person, but when she said that she demanded a public hearing then instead of taking her fired papers and going, she demanded this hearing, which was perfectly legal, she had every right to. Well, it was conducted in a very low-key way. There was the three men who were on the school committee, there was a town council and witnesses that you called in, including the FBI. And uh a man, and then various people would come with statements of one sort or another, the president of the league of women voters, of which she was a member, had to read out that she attended such-and-such meetings,

that kind of thing.

Sanchez: They, um, testified on her behalf or against her?

Wilson: They just asked questions anything she had been a member of, because she had said at one time that she was using membership in organizations to promote her ideals. Her ideas, she said, were um, goodness and light and wonderful things, but it could be interpreted that her ideals came from her membership in the communist party. And those ideals would've been translated into we're gonna fight America.

Barnett: Overthrow the government?

Wilson: Huh?

Barnett: Overthrow the government?

Wilson: Overthrow the government. Uh, that hysteria was more...it was brought about largely because of the aggressive action of some people national congress, senate and this general feeling that we couldn't trust the communists because Russia was no longer a trustworthy ally, it was an emend. And anyone who had been a communist, or who had been a fascist, or who had been anything else practically, might want to overthrow the United States government, and somehow we all had to be very scared.

Barnett: Well, so...

Wilson: Well we weren't scared...

Barnett: [Chuckles] Okay, I...uh...

Sanchez: You said that when, y'know this is like a huge y'know national fiasco

Wilson: It wasn't, it was like a minor hysteria.

Sanchez: And you said that Massachusetts kinda was pretty low-key in terms of their reaction of it, but if you look at, y'know the articles talking about the turnouts that this that these pulled in, like 700 hundred people like that seems like people were pretty upset about this...

Wilson: That's an overestimation I was there, there was no 700 people, we didn't have a place that would hold 700 people.

Barnett: Really?

Wilson: I don't know where you got that figure

Barnett: I think we got it from, um, Maynard.

Wilson: 700, are you sure?

Sanchez: I...that's off the top of my head, that could be...

Wilson: Because if it were, it would be, I'm sure that would be...

Barnett: What would your estimate be?

Wilson: We didn't have the field house, we didn't have the field house, we didn't have anyplace that would hold that many people, it is in the now town administration building, which was then the high school, and had the gym room which is were it was held and that is still...it is the large hearing room now, it is no longer a gym. And it wouldn't hold 700 people, I would say the most it could've been was 500, I think it was more like 300 people, but I am just judging from my memory and I can't... well, check it out, if it is 700, whatever he said he researched. It was a lot less the next nigh, and less then that the next.

Barnett: Yeah, we, um, read something where it said that it was the wife of Stokey...

Wilson: Edith Stokey

Barnett: Yeah Edith Stokey, and she said that her husband deliberately tried to make it as boring as possible so that less people would come so it wouldn't become a spectacle

Wilson: Well, I'm not sure how deliberate it was, um...he had to do this job because he was town council, he knew Anne Hale he knew her personally, and wasn't upset by her and knew what he had to do, and I though did it very thoughtfully, it was more dramatic than I think he expected it to be just because of the situation but he no matter how he tried he couldn't have made it boring to people really interested, but she would say that now looking back on it I am sure. I know Edith well, and she is a wonderful woman and as a matter of fact after each of these sessions they would come back to our house and rehash everything and talk it over so we heard a lot from Roger himself. I think he was deliberately low key so people would not get aroused I don't he had in m,ind keeping away by being boring, but that what he thinks of now, or maybe he told her that and didn't tell the rest of us. Who knows?

Sanchez: I'm sure a lot of people came to those meetings expecting something just fascinating

Wilson: She was a kind of doughty schoolteacher kind of person and I don't mean that unkindly, because I gather from your prom that one of your schoolteachers can dance like mad...

Barnett: Oh yes, Mr. Gavin!

BARNETT & Sanchez: [hearty laugh]

Barnett: You should've seen him!

Sanchez: He got down, so to speak.

Barnett: Yeah, he set the floor on fire

Wilson: Isn't that great?

Barnett: He honestly out-danced every student there

Wilson: [laughs] even you?

Barnett: Just barely

Wilson: Just barely, okay

Sanchez: Yeah, he put Will at a close second. You should've seen Will with his cowboy hat; he would take off his cowboy hat and put it on a girl and then dance around her

Wilson: That must've been great

Sanchez: Clever move

Wilson: Wow, we're getting off the subject

Barnett: Yes we are. But, um, you mentioned early that you were in close contact with a lot of the key players what were...

Sanchez: The key players

Barnett: Yeah, what was your impression of them?

Wilson: Well, I was just about to tell you about Anne Hale. She was a kind of doughty person, she wasn't sharp like your dance teacher, that's why I said sorta school teacher-y, just an image of kinda short and a little, y'know, not very shapely, and just a kinda cute little thing. But she wasn't, she didn't give me the impression of being firebrand or anything like that. The school committee, well two of them were fairly elderly compared with the rest of the population that was attending this and one was a young, in those days, young labor lawyer and he was really kind of an exciting personality, he didn't look it. He was a big tall langely y'know, and, but he was kinda...he was really...actually he voted against her being fired even though he recognized the seriousness of signing something and telling a lie on paper and afterwards in person but she did admit that she had been a member of the communist party, but no longer was. That's the part a lot of people weren't willing to believe. But the technicality on her being fired was the fact that not telling the truth at the time of her application and repeatedly when signing tenure papers and so forth. She never admitted to her membership, her prior membership; whether she was still a member or not I don't think was ever proved, and I don't know how you prove if you're still a member of something that is clandestine as that.

Barnett: Right. But, uh, yeah, back to Stokey, what was he like?

Wilson: Well, he was prematurely balding, very young looking, however, because he had light colored hair, blue eyes, pink cheeks. A real young looking guy, but very, very...you knew right away when you met him that he was highly intelligent and a person of considerable integrity. Um, the guy from the FBI looked just like a guy from the FBI...

Sanchez: [Chuckles]

Wilson: [Chuckles] He tried to paint him, dark suit, dark tie

Sanchez: The suit

Wilson: Tall, upright, salute the flag, I mean he was really one of those people but he was very good. Um, most of the other people were people who have known Anne Hale as a schoolteacher, some of the schoolteachers spoke in her favor, some spoke that they weren't sure what they would've done. Not a long list of witnesses, the most exciting thing of course was getting the FBI involved.

Barnett: Right

Wilson: And a lot of things were read into the record, um, the report of the legislative commission that had named her as a communist. But it was more perfunctory than dramatic. It was really not all that interesting.

Sanchez: Do you think that the people, the people from Wayland walked out just feeling let down, like "Ahhh, I wanted to see some action" or

something like that?

Wilson: Well...

Sanchez: Or reading of some paper?

Wilson: I think that, I think most people felt that it was well that this had been handled the way it was. Most, there was certainly not much comment after this, as you know from looking at the Criers. It didn't go on and on like some continuing story. Everyone just sorta picked up their business, and that was it.

Barnett: And you mentioned, uh, earlier to me that you talked, discussed the case every night...

Wilson: Afterwards after we got to our house, the reason we choose our house is because [chuckles] nobody would have known where it was, it was on the upper part of Gleezen lane, and, um, and nobody really knew we were there, we had only lived in town for three years or so, and so the Stokey's car or other people's car would have been recognized. They didn't want to mean at their house because that was right on the main drive on 126, and everybody would've know there was a gathering there and wondered what was going on. So... [chuckles]

Sanchez: Could they be changing their drapes?

Wilson: [Laughs]

Barnett: Painting the house red?

Wilson: No we didn't! But it was, you just didn't want to take any chances with anyone reading anything wrong. mostly it was a chance for Roger to take his shoes off and relax because he had been under a lot of tension to be sure he was asking the right questions and doing the right things. And he...

Barnett: So you sorta gave him feedback?

Wilson: So we were able to say, y'know, tomorrow night or maybe the next night you ought to ask this question or...that kinda thing. That give and take. The...I think that what everyone was trying to do, who was involved, including the school committee, was to have a fair open hearing at her request. They really didn't want to have an open hearing; they really wanted it to be just "goodbye Ms. Hale, it's been nice knowing you" but she insisted on having this because I think that she felt that if she could prove to them and the public that her prior membership to the party did not affect her teaching. And I am sure she made that clear. And for that reason and nothing else she felt vindicated, even though she was fired.

Sanchez: She can save face knowing that her personal character

wasn't...

Wilson: People would not go home thinking that she was an evil person. And if it had been done in private they may have had the impression that she was admitting some kind of guilt. So this way she was able to have her say and have the public recognize that she an, um, non-horrendous devil in someone else's clothing, she was really a decent human being striving for a better world. And her thought...her idea for a better world included some things that most people who were upward mobile people who went to a community like this would think of as being backward, anti-democracy, anti-government, anti-business. Y'know the things that communists were known to be

Barnett: So, this trial it seems very rational, very nice, so it seems like the opposite of the McCarthy hearings

Wilson: It was so different, you're right, that was a table pounding extortion. It was really, uh, a very...very bad thing to have done in my opinion, and it caught people's fancy because it was the first time that this kind of think had been done in a public media. Y'know TV was brand new, radio was the big thing, it was hard for people to adjust to the idea that the country could be seeing and hearing someone who was a real dema--demagogue and his...his coworker Cohn, the lawyer who was...

Barnett: Yeah, yeah

Wilson: Was a bad man in my opinion. And they did a lot of damage to people's reputations. A lot of good actors and public people got vilified that shouldn't have been. And it was not an unpopular thing to be a socialist.

Barnett: Right, during like the Great Depression...

Wilson: ... Socialist and communist it's not...It's extreme in those in the mind of those who know but in the general public that's bad.

Sanchez: How much did the people in Wayland know about communism, or the ideals...I mean that she published the ideals that she stood for and tried to instill in her students, but you have to wonder how much the people of Wayland actually knew?

Wilson: I don't think that very many people did because it wasn't the fashion in those days to, um, devour Marx.

Barnett: [Chuckles] Yeah

Wilson: it was not, y'know, it was not...um...I think that some, there were definitely some people in town who truly believed that there were a lot of communists hanging around in this community and they were evil people and they should be thrown in jail because they were out to upset their pattern of life. And they felt, I think, a little cheated that this didn't get bigger play and Wayland didn't get more on the map for having...

Sanchez: Fought the good fight.

Wilson: Remove this dangerous woman and so forth. It really did not make a lot of play, and that is why I thought that page in the Town Report that...

Barnett: Right...

Wilson: Two sentences is all... Well y'know, this think that would've, you would've though from the first 10 lines that the entire town would be in a great state of upheaval...

Barnett: Yeah, well with Maynard's essay he calls it "The Red Scare In Wayland" and you get the sense that its this massive thing, and the way you're describing it, it really sounds like nice, I mean not exactly kosher by today's standards, but...

Wilson: Well, it was certainly...it was certainly nicely done, as I way of saying that I think that Anne Hale's point in having the open hearing was vindicated. Everybody could understand who listened and paid attention that she was trying to prove that a point and she was able to do that. But she could not erase the fact that she had been dishonest with the school committee, and they couldn't erase the fact that she had signed these papers. I don't know what went through the minds of the school committee members themselves, except for Walter because I didn't know the other two well enough to...yes?

Barnett: No, just, no, well Walter, what was he thinking?

Wilson: Well because I had worked with him before either of us had moved to Wayland, in past experience he had been a labor lawyer for a union who was trying to get its way into a department store, but I was on the administrative end of it, so that he and I were in conflict with each other. But I must say that he never raised our voices and yelled at each other or anything like that. I respected him, and I think he respected me. But his feeling was that he...he was willing to overlook a...minor infringement, in his idea, because she was a good teacher, and shouldn't do that. Barnett: Didn't he say though, um...

Wilson: Afterwards he did

Barnett: That, um, if she, if he had been able to count the silence that she said against her, he would've voted guilty?

Wilson: Yes, that's right. He did, he did say that...but reluctantly...um, he wasn't reelected to the school committee, and that may have had something to do with it.

Barnett: So, do you think there was a real, uh, kinda...not McCarthyism, but a McCarthyist attitude?

Wilson: There is no question that there were certain people in town, and most of them are no longer alive that I can think of, but there was this one man named Frank Carter, and he was very sure that not only was she a communist but there were a lot of other people, most of those people lived in red houses...

Barnett & Sanchez: [laughs]

Wilson: Or did things with their shutters, or what else, but they were communists in his mind and they were gonna try to overtake, and that was a very interesting thing because, um, the kind of thing that got said, sort of with tongue in cheek, that the guy at the post office, let's say; we didn't have delivery then, we had to go to the post office everyday, and one time I was in line with another person, I was at that time on the board of health, so I was an elected town official, and so was the guy behind me, and the post master was chatting about this, and he said "Well, it's these new people coming into town" the guy behind me had lived in Wayland for a longer period of time than I, said "they are just gonna take to take over everything" and then he recognized that I was there: "Oh, I didn't mean you of course", so he did mean me...

SANCHEZ & Wilson: [laughs]

Wilson: We were, y'know, anyone young coming into a community is gonna be radical, just by virtue of being young.

Barnett: Right

Wilson: And I wasn't gonna go around talking about pretend communists behind trees so therefore I might be doing some evil too. But not just myself, a general feeling that anybody who had fresh or different ideas might be dangerous; there was the little atmosphere because of the McCarthy stuff that had permeated, so that people...even if they didn't want to, might label somebody a...."Oh, he's probably a communist"

Sanchez: Do you think people did that out of protection, that, "oh, they might think that I am, y'know, up to something, or am a pinko"?

Wilson: That's a very clever analysis. Yes, probably some of it was. If I say something like that then people will know that I'm not a...yeah, there was probably a little of that kinda stuff: maybe almost subconscious. That's...that's very searching.

Wilson: It was not as...well, particularly now that I look back on it, it was not anywhere near as exciting as it could've been. It was really quite low-key

Barnett: [inaudible]

Wilson: And that was Roger Stokey, he, and the school committee themselves, and the tenure of the town because even though there were some people who were.

Sanchez: Subscribers to...

Wilson: Were scared by anything red there were a whole lot of people, there were some people who weren't, and there were some people who just plain didn't care. It just didn't make that much difference, because they didn't have a child who was affected by this teacher, so things were getting taken care of. Probably the most, the largest attendance the first night was just plain curiosity; how's it gonna be done? And then when they saw it was not as interesting as...what they might see on television at home [coughs] they just sorta dissipated...and after it was all over there was very little reference made to it except when somebody would be discussing things in the past, like now...

Sanchez: Ha

Wilson: Part of this is just because of the year, the time or because..

Sanchez: Because it plays into, y'know, Wayland's a small Northeastern town, it might have something to do with the country at this time period at large, so pretty much yeah, just the time period...[coughs]

Barnett: What was the '50's like?

Sanchez: You mentioned something about TVs

Wilson: Let me...Most of the people who moved in new were a bit like ourselves, who moved in...in 1952-53, around there, were people who had not, many of them [inaudible] first of all, they were young adults with either starting their families or...or babies or had a dog and couldn't keep it in the cit, or something and it was a step up, from living in an apartment in Cambridge or wherever they had been, to coming out here. So a lot of people were, and this had been a very rural community until...ah...much more so than Weston, even though 128 didn't divide things then, anything that was west of what is now 128, except for Weston and parts of Needham was...were unbuilt to the extant they are now. So there was a lot of housing going up. In that particular period of time all of the section we now call happy hollow and Damend Farm and Woodridge and some of the other sections or houses or...were almost all built at once and then everyone moved in so the whole climate suddenly became young parents, or about to be parents. So there was a big impulse to get the schools up to snuff we had at the point a school superintendent we shared with Sudbury, we didn't even have our own superintendent. The building that is now the town office building was the high school and the junior high school. Um, happy hollow had been built, was built this year, I think, the same year as '54 maybe '55, but the happy hollow school was either under construction or about to be. And, well I'd like to remark I remember a couple with like four boys and they said "we can't afford not to have a good school system" In other words we can't send our kids to private school, we got to many of 'em and don't make enough money so we are gonna have to have a good school system, and that was the attitude. There was a lot of attention paid to the school and school events...um, volunteering fore...many women didn't work outside the home, because they...because that wasn't the going thing then and so they were home all day, so there was a lot more volunteering, so that organizations like the Junior Town House, the league of women voters, other organizations, that were very active. A lot of volunteer effort, cub scouts and things like that were real big. I would probably say your cub scouts and um...

Sanchez: [Inaudible]

Wilson: Campfire girls, and things like that were big groups of people and much more than they are now.

Sanchez: Yeah...

Wilson: There is a Boy Scout troop in this town I think...

Barnett: Yeah, there's not many kids...I mean not that I know of...

Wilson: But it is just that it was the thing, I mean all things that keep the kid occupied after school, no school clubs either. There weren't things like that at high school, there weren't...there was a football team, never won any games or anything...

Barnett & Sanchez: [Laugh loudly]

Wilson: But until the new high school, then new, now the almost 50-year-old high school, was built, high school activity was minimal, I mean there really wasn't a lot of after school stuff to do. The bandleader that came about around then, he really charged things up and got people interested in music. But it...it was a slow process, I mean it seems so to us who want everything now. I think that was probably the thing, when you're growing, when your town is growing, there is an excitement about it that you don't feel now...there...young parents who were really excited about things, they went to everything, babysitting was something that was done all the time, high school girls babysat nightly.

Sanchez: I'm sure...I'm sure that's a way that every family got to know every other family, just by babysitting each other's kids, y'know...y'know?

Wilson: It was...It was a different pattern....

Barnett: Was it, wait, was it a close-knit community at this time?

Wilson: Those who were involved was very close-knit, um, In a way that I think probably will never happen again, in this kind of...uh...community. There were the old townie Cochituate people who just didn't like any change going on at all, thank you very much...

Barnett: [laughs] Still the same way

Wilson: There were old farmers in the Northern end of town who didn't want anything to change and reluctantly began to accept the fact that it was changing; they couldn't do anything about it. They tried, and...

Sanchez: What do you mean by "they tried"?

Wilson: Well...they...[Side A of the tape runs out] [Side B starts, small elapse of time] involvement, but then there were too many new younger people that they got swamped.

Barnett: Yeah

Wilson: And so, pretty much things ran the way people with young children, in public schools, wanted them to run. We got an expensive superintendent, we got an expensive new high school, we got three elementary schools, all brand new practically, and they really couldn't do anything about it.

Sanchez: They just had to accept...

Wilson: Accept the fact that their property values went up...

Barnett & Sanchez: [Laugh loudly]

Wilson: And they had to pay more taxes, but they didn't like any of that. Now, that was a handful of people, I mean, in comparison... Barnett: Right

Wilson: But they were vocal

Barnett: They were the loudest?

Sanchez: It is always the angriest that are the loudest [laughs]

Wilson: It is hard to give up a feeling of ownership, when you feel you're an active old timer in town and really run things, and then you begin to find all these thirty year old people are running things, then suddenly you just feel left out, as if...and you're resentful. I think some of that happened, not a lot of it. So, it was more exciting I think for people living here then because, well, I can't say that because I don't really know, but it seems to me, that when, um, I think that the young mothers in town exerted a lot more influence then they do now, in proportion to the population. Because they were actively involved everyday in the town, there wasn't any kindergarten, so they had to take their children to private kindergarten, kindergarten that was absorbed, but at the time we are talking about, it wasn't public kindergarten. And then they got into carpool kinda thing, and there were all these activities that came after school, and so the mothers were driving people that...children, all over town and there was a lot of give and take, um, again as I say there wasn't the organized clubs at school, or music lessons, so that the people weren't involving their kids in that sorta thing. Probably no more quote "together" time than you have now, because of the various kinds of, almost frenzied activities that these mothers were doing rather than going to work someplace and getting paid for it.

Barnett: Yeah, that's interesting

Wilson: What else, anything?

Barnett: Well, uh, it seems that, uh, Anne Hale case was not this big of McCarthyism in our town which we were kind of believing until now, but we would both like to know if there are, were like any lessons learned there that should take now to out times

Wilson: Well the biggest lesson of all of course is one would hope that we had learned as a country that you don't trust demagogues. But I'm not sure that lesson every got learned, except for one generation, but it didn't get passed on very well to the next. Uh, I think that we're still on the, that human being are still at the point were we tend to believe people who sound as if they know it all, and there is not enough questioning, but that is my own public, my own private opinions. I just think people ought to question everything. But...that kinda of attitude is what back then would have made you seem like...

Barnett, Sanchez & Wilson: [laugh loudly]

Wilson: You're no good

Sanchez: That's red talk!

Wilson: But I think that...that...poor Anne Hale never, of course went on to have a miserable afterlife, she never as able to get the kinda job she had here that was...as good as this. And she kinda...um, y'know, didn't have a rosy after-Wayland life.

Sanchez: Did she keep in contact with Wayland at all?

Wilson: Some people have...had kept in contact with her, uh, particularly the people who were involved with the Unitarian church, who did want to befriend her because she was a member of the church. And that was another thing that happened to, for a while there the Unitarian church was thought of as being a hot bed of communism, because the minister was young and Anne Hale was a member and people were standing up for her and she was still allowed to go to church, believe it or not, nobody closed the door on her, so therefore she must be...they must be a hotbed of communism. But that dissapiated too, obviously; I don't think that people think that the Unitarian church is harboring....

Sanchez: Oh those Unitarians, up to no...

Wilson: [Inaudible] Government....

Sanchez: Up to no good!

Wilson: [laughs] Up to no good. So it was all, y'know, there was...there were little fringe things that kept on from this that didn't really disappear until...until McCarthy was shown up to be ridiculous

Barnett: Yeah, he fell hard

Wilson: And that...that took a while. Um, when you elect somebody to a public office, they are gonna last up their term, and there is nothing you can do about it.

Barnett: But he can be censured

Wilson: [laughs]

Sanchez: Did you know anyone or did...yeah, did you know anyone who was really just adamant about McCarthy, just loved him, just thought he was doing such a good job...?

Wilson: Well yes, well, Frank Carter, that I mentioned, and there were others, but they...but her was really...he...he was a dyed in the wool, um, communist-hater. And anything that tinged of red-scare was enough to get him really uptight. And he could talk, there were people like him in town, but we were lucky enough that there weren't many. And...it was big in town, of course, but it was much shorter lived and much quicker forgot than people would have thought in the beginning of it, and everybody was adjusted to the fact....as...as they say everything was growing, more and more kids were coming, schools were being built, things being taught, there was the Strawberry festival, there was the memorial day parade, where everybody turned out, there were things that were happening, there were less influential now because we don't have those same things, or the need for them quite the same way, uh, perhaps, so that, um, you can forget the things, y'know that just...

Barnett: Sorta just washed away?

Wilson: ...everyday wake up and say "Oh, that poor Anne Hale!" or "I'm

so glad we got rid of her!" it just didn't matter much...

Sanchez: It just sorta left with her, y'know? Just the whole topic of discussion...

Wilson: well, y'know everyday there's another little something that happens, so you don't just keep dwelling on something that's...it was publicly taken care of, it was handled without rancor or screaming or flag waving, it was quietly, as you can tell from your paper, y'know, next month there was something more important, or as important. And this town, being this far away, in those days, from Boston, we were a little hick town compared to what was happening there, so, uh, the Boston Globe might've had a piece on it, but it wouldn't have been the top headline, something that was happening in Boston would have been much more exciting...

Barnett: I'm sure they had their own communists...

Wilson: Huh?

Barnett: I'm sure they had their own communists!

Wilson: Yes, they had their own communists! You're right, and they had other things which were happening, so, um, y'know, it was...everybody in the country was concerned about red China, communist Russia and of course there was the whole USSR, so it wasn't just Russia. And what was left of...of...y'know...un...un, the people who hadn't quite been quelled of their fascist notions in Italy and Germany. People were much more concerned with idealist...different kinds of idealism in other big foreign places, so that gradually, I think most of the country began to realize that this country was not about to be overtaken by a few Gregory Pecks or whomever...[laughs]...it just wasn't going to succumb to some foreign idealism that wasn't proper for this kind of a set up, with, a democracy isn't just gonna give in to a few people who want to change things that much. And so they relaxed a bit. Okay?

Barnett: Yeah, why thank you!

A transcript of an interview with Rosalyn Kingsbury,

a

Wayland resident who knew Ann Hale.

Sanchez: Did you know anything about Ms Hale before the Trials began?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Oh yes my son had her as a teacher.

Shaw: Oh thats so interesting. Sanchez: [At the same time]Oh really?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Yeah yeah.

Sanchez: Do you remember any of her classroom antics or anything along those lines by any chance?

Mrs. Kingsbury: She was a very good teacher. one of my sons had her. I guess it was Keith, the oldest son. I have three sons. And I went down and helped her in the classroom as a mother helper.

Sanchez: So you got to work along side her?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Yeah, I didnt go very often. It was when she had something special she wanted to do with the children. [chuckles] The one thing I did was arm wrestling.

[Everyone laughs]

Sanchez: Well thats kind of cool she had arm wrestling day for the kids...

Mrs. Kingsbury: Hm, something like that.

She was a good teacher. She was a very nice Mrs. Kingsbury. She was unfortunately a very lonely person and was just sort of- found friends (from a very good family too) found friends that were very kindly and became her friends but they were just...

Shaw: Not very close.

Mrs. Kingsbury: Well, I think they were worried about the communist group that she seemed to be unaware of it being they were friendly to her and she was shy and so they became her friends and there was something else that was brought in by this group. And thats why she got a bad name. It was too bad she was a nice person.

Shaw: Hmm.

Mrs. Kingsbury: She was really, I feel, quite unaware of the-

Sanchez: What she got involved in or how it got out?

Mrs. Kingsbury: I dont know. As I remember she just seemed to be in that group. I think she just didntÖ She was really unaware of... that it was wrong, that group of friends. She didnt probably defend herself.

Shaw: Hmm right.

Mrs. Kingsbury: Or maybe even understand.

Sanchez: Do you know any of those friends? Do you remember anything about them?

Mrs. Kingsbury: No No I knew nothing about them. It wasnt until she was- oh the start of the trial wasnt it. I think my brother was one of the lawyers, and Mr. Stokey. They worked together.

Shaw: Oh yeah?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Now theres a paper that was written by a member of the Unitarian Church that describes the whole thing very very well.

Sanchez: Mr. Mainer.

Mrs. Kingsbury: Hmm?

Sanchez: Robert Mainer is a member of the- he wrote the-

Mrs. Kingsbury: Oh yeah hes the one who wrote it, absolutely.

Sanchez: They used to think back then that the Unitarian church was just this, like, “My partner Wills grandmother, Jo Wilson, said that, um, people used to think the Unitarian Church was this hot bed of communism.”

Mrs. Kingsbury: That right, they did. Thats about the time I joined.

[Laughter]

Or just after. Well there were some people who were very liberal and... and thought of... um...

Sanchez: They gave people the impression of?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Yeah yeah of being liberal. This town was not a liberal town.

Shaw: Hmm.

Mrs. Kingsbury: -and the Unitarian Church- well not every body but because this is a very old and well known church and there are a lot of fine families in town that are Unitarians. But it was considered quite liberal and so anybody can seem to be um interested in associations that had to do with human rights and that sort of thing were kind of...

Shaw: Out of the loop?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Yeah. Pointed at.

Sanchez: Really? Anything that had to do with just human rights?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Not just- well no I think thats just the way I looked at it. Because some of my good friends were people who were involved in something called Fair Housing.

Sanchez: Yeah Fair Housing: it was so they couldnt discriminate against people trying to buy a house.

Mrs. Kingsbury: Yup. Now thats good thinking.

Sanchez: And those people were pointed out or singled out?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Some of them. Some of them. It was a pretty conservative town.

Shaw: Thats funny how Wayland's become so, I mean for the most part, liberal now.

Sanchez: What was it that drew you to join the Unitarian Church?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Well I think the Reverend Daniel Finn was at the Unitarian Church. I started out at the Congregational Church because the home which I came from the Congregational Church is the one I went to. So when I came to town and put Keith in the Congregational Church he was quite shy. At the end of the year I received a letter from the church saying theyre sorry that my son had not attended and hoped that he would return in the fallÖ and may god be with you or something like that. We though [chuckling] hed get a gold pin for attendance. So thats how much they paid attention to the school board he was very shy. So I learned about the Junior Church at the Unitarian Church which seemed to have a wonderful- Dan Finn is a wonderful preacher. He and his wife organized the Junior Church so that the older children would set up an organization just like the senior church. And teach them to be responsible and that sort of thing. It just seemed like a program that made more sense to my husband and me for him. And then I enjoyed it too.

Sanchez: Did Ms. Hale recognize that your son was a little bit shy; was this something she pointed out to you?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Of course, she was veryÖ He was young, actually. His birthdays in November and he was really shy. We felt he was ready; he was beginning to read and we were not at that timeÖ we were anxious to get him into school. Thinking it was the thing to do. We thought we were doing the right thing. Actually we should have brought him to a private kindergarten.

Sanchez: Why do you say that?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Because he was young and immature and shy. And now a days they dont start children, nevermind the age, you go when youre socially ready. I taught kindergarten for a long time and selected children from nursery school to go into kindergarten when they were ready.

Shaw: So Mrs. Hale-

Mrs. Kingsbury: Ms. Hale

Shaw: Miss Hale, she handled your son...

Mrs. Kingsbury: He loved her. Yeah, she was very very nice.

Shaw: She wasn't impatient or anything?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Oh no. not impatient. She was just a lovely person with children. As far as we could see.

Shaw: Right yeah

Mrs. Kingsbury: I've never heard of anybody, in fact it was just that year that anyone had any problems.

Sanchez: Were you caught by surprise when... how did you find out that she would be put on trial?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Oh it built up. My brother was involved and some people were complaining because she was involved in this group. And felt that she was not suitable to teach. The whole thing to me seemed quite unfair.

Sanchez: You say there were people that complained, like they were a group of very vocal citizens?

Mrs. Kingsbury: I gather so. You know I was unaware of that because everything was so successful: With the children and the nursery school and kindergarten they were in. Finally I was on the board of the Junior Town House for kindergarten. Once your child goes beyond kindergarten you cant be on the board, school board. So I was just a mother at home until- lets see why did... oh I know, one of the teachers died- and I had a teachers certificate so they asked me to teach. I've been teaching ever since, until I retired. I actually have a therapeutic dieticians degree. I went to college and then graduate school.

Shaw: Oh really?

Mrs. Kingsbury: But I had three little boys and I wanted to stay home with them and I thought well I like children so I'm going to go on and do this.

Sanchez: There weren't a lot of women, er, mothers that had jobs at that point?

Mrs. Kingsbury: No not like that.

Shaw: But teaching was a common job for women.

Mrs. Kingsbury: Yeah. It was just being involved, it was something that I was able to do and to do it for the children.

Sanchez: Did you ever get to see any of the trials when Ms. Hale was put on trial?

Mrs. Kingsbury: You mean went to the meetings? Sure. My brother was part of the scene.

Sanchez: Can you describe those?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Uh well it was just questions and answers and it was held at the High School- old High School Gym which is now the town building. We all sat on the bleachers and there was a moderator. I think Roger Stokey might have been the moderator.

Sanchez: What was the atmosphere like? Was it exciting?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Curiosity. That was the big thing. We were a small town. My oh my look whats going on. It was very well run. But it was um...

Sanchez: Did people come to the meetings with very strong opinions about her?

Mrs. Kingsbury: I suppose some did. I think most of my friends certainly thought it was unfair. That it was too bad it was happening in a small town.

Sanchez: Do you remember anyone who was just adamantly against her?

Mrs. Kingsbury: No I dont. I think there were some people who might have been... no, I dont know anyone who was adamantly against her. I think there were people who felt that she was being unfairly criticized. Probably because she was so nice and got along so well. I mean we have three little boys and were interested in doing the right thing by schools and kindergartens an ooh. There were a lot of stay at home mothers. It was a while when I was well into teaching there were a lot of divorces in town. The town had grown, there were divorces. Mothers were working, and thats when I did most of my teaching in the public school system. That was some of the problems there, well after I got involved in the junior town house. As the town grows different problems come up. They're handled differently. The staffs change.

Sanchez: Have they changed for the better in your opinion?

Mrs. Kingsbury: Oh Yes. The school system was really very good and it still is. But we worked hard for it.