- Anne Hale: The Case of the Communist Teacher

- Baseball: A Way of Life

- Chuck Taylor Hightops: WHS Basketball

- The Baby Boom Explodes

- "Mrs. Everywoman"

- Warriors Football

- Nightlife Up in Smoke: The Mansion Inn

- Not-So-Fast-Times at Wayland High

- The Sirens of Wayland: The Police Department

- Cold War Wayland: Nike Missile Site & Raytheon

- Keeping Up wit the Joneses: Consumerism in the Town Crier

- A Sense of Community: The Strawberry Festival

- Newsletters to Those at War: The Bugle and the Jeep

- A Quieter Life: Coming Home from World War II

- Duty Calls: Veterans of the Korean War

- A Simpler Time: Growing Up in Wayland

- Old Meets New: Dudley Pond

- Flash Movie

Cold War Wayland: Raytheon

|

Jump to Nike Jump to Pictures |

|

Mr. Sweitzer Interview Audio Segment |

With the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War and the nuclear age, the United States was a fast changing place. The United States was continuing an arms race with the Soviet Union and there was much interest in development and manufacturing of weapons by the government and by private companies. The United States government was spending billions of dollars on new military technology and hardware. Companies like Raytheon needed to compete by building new labs to develop the technologies that the government wanted so that it could win lucrative government contracts. Large areas of land were needed by these companies to conduct research and testing on new weapons. This meant that small towns like Wayland that had been based on agriculture and small business were now the center of what President Eisenhower called the "Military industrial establishment." But Cold War spending did not just affect Wayland, thousands of towns just like across the nation saw similar industrial developments that had never been seen in small town American before.

With the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War and the nuclear age, the United States was a fast changing place. The United States was continuing an arms race with the Soviet Union and there was much interest in development and manufacturing of weapons by the government and by private companies. The United States government was spending billions of dollars on new military technology and hardware. Companies like Raytheon needed to compete by building new labs to develop the technologies that the government wanted so that it could win lucrative government contracts. Large areas of land were needed by these companies to conduct research and testing on new weapons. This meant that small towns like Wayland that had been based on agriculture and small business were now the center of what President Eisenhower called the "Military industrial establishment." But Cold War spending did not just affect Wayland, thousands of towns just like across the nation saw similar industrial developments that had never been seen in small town American before.

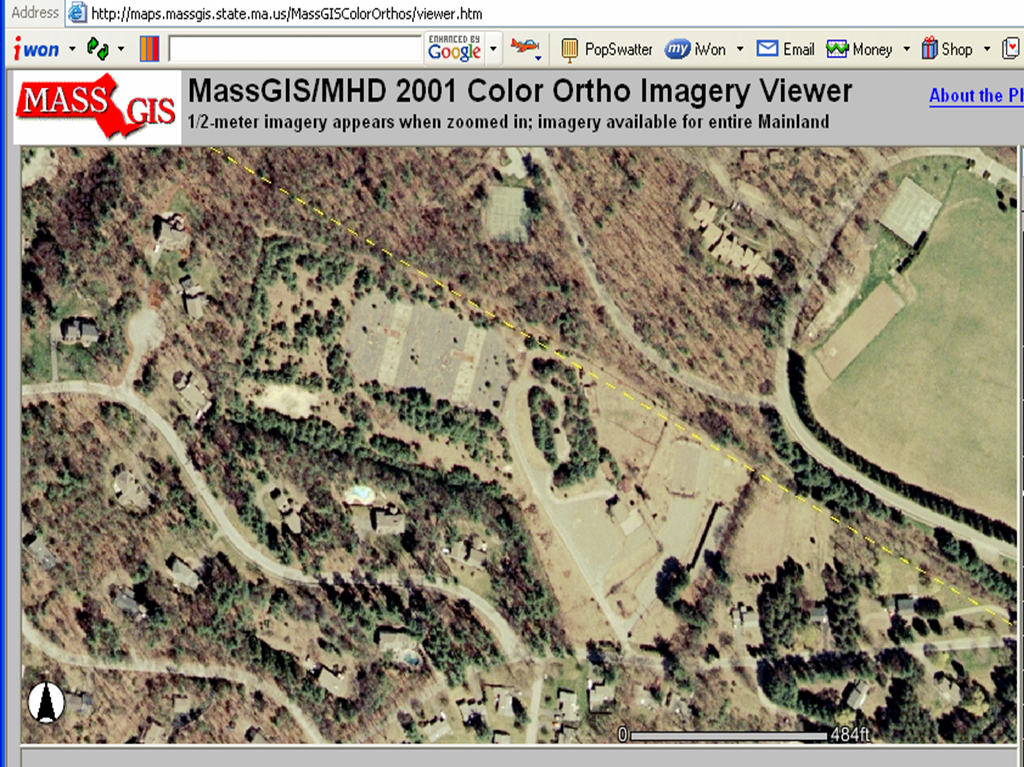

But why Wayland? The Raytheon Manufacturing Company was looking to build a laboratory near its headquarters in Waltham Massachusetts. They needed a large piece of land that would allow them to build a laboratory and that would be convenient for their employees and a place where they would be able to expand in the future. The laboratory that they planned to build would be used for the research and development of naval equipment, mainly missile guidance systems that went into missiles such as the Polaris and Trident missiles. Raytheon was also looking in neighboring Sudbury, but had decided that Wayland best suited their needs. Raytheon was interested in the 83 acre farm site just west of Sudbury road because it had everything they needed to build a laboratory.

But why Wayland? The Raytheon Manufacturing Company was looking to build a laboratory near its headquarters in Waltham Massachusetts. They needed a large piece of land that would allow them to build a laboratory and that would be convenient for their employees and a place where they would be able to expand in the future. The laboratory that they planned to build would be used for the research and development of naval equipment, mainly missile guidance systems that went into missiles such as the Polaris and Trident missiles. Raytheon was also looking in neighboring Sudbury, but had decided that Wayland best suited their needs. Raytheon was interested in the 83 acre farm site just west of Sudbury road because it had everything they needed to build a laboratory.

But it was not just as simple as buying the land and building the facility. First Raytheon had to get the town to change the zoning laws on the land that they were interested in buying. At the time, the 83 acre tract of land was zoned for residential use. Raytheon needed the town to change the zoning laws to "limited commercial district." There was much division within the town. Many citizens of Wayland thought that by welcoming this industrial facility, Wayland would be losing its identity as a quiet country town. The opposition to the facility was led by "The Home Owners of Wayland" which was composed of a group of residents who believed the facility would be damaging Wayland's image as well as welcoming traffic and an increase in population. Despite the opposition to the facility, there was a substantial amount of support for it as well. Some of the arguments were that the facility would give the town tax revenue that it desperately needed. Also, if Wayland did not allow Raytheon to build its facility there, they would build it in Sudbury and receive all of the traffic without any of the benefits from tax revenue. Another positive aspect of the facility would be an increase in highly paid residents. People that would pay a lot of taxes without putting strain on Wayland's finances. It was also promised by Raytheon that the facility would only be used for research and there would be no manufacturing, therefore limiting pollution.

On March 3, 1954, there was a town meeting at which the people of Wayland would vote whether or not to change the zoning laws on the 83 acre farm land. The citizens debated for 3 hours and when the issue was finally voted on, they decided that the zoning would be changed with a vote of 733 in support to 167 against. This vote marked Wayland's transformation from a small quiet town to a town with a major industry; this was a change that was taking place all over the country, not just Wayland.

Raytheon was a good neighbor for the people of Wayland to have. The plant employed 1050 employees with a limit of 2,000. It paid the town millions of dollars over the years ($54,000 the first year, almost 6% of Wayland's tax revenue for 1954) in tax revenue and supported the school system and the town library. Raytheon donated money for the building of the Raytheon room at the town library and let the schools use some of its equipment.

Raytheon worked closely with the town when complaints surfaced or when changes were made to the Raytheon site. Although there were some problems, such as noise and light complaints, Raytheon took the time and effort to fix those problems and be the best neighbor that it could be.

During an interview with Harry Sweitzer, who worked at the Wayland plant, we asked if there was any pollution or spills he knew of and he responded,

"Well, the energy from the radar goes out. We would reduce power and see to it that the radar didn't hit the ground until a ways out. Nobody knowingly polluted the atmosphere or the ground or anything like that. Raytheon was responsible for what was determined pollutants. They've been (been) going through a great exercise digging down and hauling that stuff off the site."

We also asked him about complaints and conflicts with the town that Raytheon had. He said, "Certainly not noise because there wasn't any noise. Sometimes things like lighting at night, and when there was something we would try to do something about it. We would lower them or put metal shields over them. I'd say, in general, relations with the town were pretty good. The human resources people were very much interested in that kind of thing. As was I because I lived in the town. We tried to reach out to the town. A few of us would sit around with some high powered folks in the company, and we would try to figure out what we could do to reach out to the town, to reach out to the kids, to reach out to the old people. Practically every year we had an open house. We would open it up, and people could go in."

"Well, the energy from the radar goes out. We would reduce power and see to it that the radar didn't hit the ground until a ways out. Nobody knowingly polluted the atmosphere or the ground or anything like that. Raytheon was responsible for what was determined pollutants. They've been (been) going through a great exercise digging down and hauling that stuff off the site."

We also asked him about complaints and conflicts with the town that Raytheon had. He said, "Certainly not noise because there wasn't any noise. Sometimes things like lighting at night, and when there was something we would try to do something about it. We would lower them or put metal shields over them. I'd say, in general, relations with the town were pretty good. The human resources people were very much interested in that kind of thing. As was I because I lived in the town. We tried to reach out to the town. A few of us would sit around with some high powered folks in the company, and we would try to figure out what we could do to reach out to the town, to reach out to the kids, to reach out to the old people. Practically every year we had an open house. We would open it up, and people could go in."

Back to top

The following is a full transcript of the interview with Mr. Harry Sweitzer

|

Will: Please state your name for the record. Harry: Okay my name is Harry Sweitzer. Everybody's called my Skip since I was born, so Skip. I live at 34 Hill side Drive in Wayland. We moved to Wayland in 1959, when I was working for Raytheon. Will: When did You start working for Raytheon? Harry: 58, no 57 or 1958, I forget. Will: What town where you working in? Harry: That was in Bedford. We had a laboratory in Bedford, which I don't think is there anymore. Then I worked in a place called Winter Street, there was a building for Raytheon. I worked there, and then I worked up at the Bedford labs. Will: What was your job at the Bedford labs? Harry: Well, I was a specification writer. What was involved in that particular job was to write a purchase specification for a particular piece of equipment. It could be a transformer, it might be a transistor, it might be a hydraulic pump, it could be almost anything, and it was a descriptive document. It listed suggested vendors on it because the engineers would try various piece parts, and the ones they liked, they would tend to write a spec around that and recommend vendors. When whatever it was that the parts were going into would go into production, there would be a series of documents a mile high and the parts list would be on the blueprints. Then they would use those documents to go out and buy the parts. Will: So it was saying what needed to be purchased and from who in order to build something? Harry: Well it might be to build a sparrow missile, it might be a hawk missile, it might be a piece of fire equipment, it could be anything. Will: Did you ever live in Wayland and work in Wayland at the same time? Harry: Yes I did. Will: And that was in 1959? Harry: No, that wasn't until the seventies. I went there from the plant in Sudbury on route 20. I also built the plant in Marlborough. Will: You built it? Harry: Well I mean I was in charge of getting it built, which I've never done before. That was exciting. It was a very interesting project. It was about a 65 million dollar project. We had to do a big job on making a highway out there, through Marlborough, accessible. The road had to be widened, and traffic lights had to be put in because there were probably 2,000 people who worked there, so there was a lot of traffic. So that all had to get designed, and we built that and the laboratory. Will: When were the exact years that you worked in Wayland, or were they on and off? Harry: Let me think about this. I worked a long time in Sudbury, and in Sudbury I was working on the guidance computers for the fleet ballistic missile submarines. The missile itself. We worked with the Draper laboratory which was part of MIT, and we designed the guidance systems that went into the polaris and trident missiles. We actually built and manufactured the stuff in the plant in Waltham. The next project I worked on, which was really fun, was the Apollo program. We built all of the computers that went to the moon. Everything on the Apollo program, Raytheon built. And that was in collaboration with MIT as well. It was a really fun program. We had the astronauts going through the plant. It was really neat. It's the most fun I've ever had, and I've never worked so hard in my life. Because the name of the game back then was whatever it took, you did it. If you worked 100 hours a week, you worked 100 hours a week if that's what it took to get the job done. Now, that sort of thing was for professional people who graduated from college. You worked however long it took to get the job done. Sweitzer ClipWill: How did you get to Wayland? Harry: When I first went to work for Raytheon, I lived in Wakefield. I really liked Raytheon, and I figured I wanted to stay with them. We decided we wanted to move from Wakefield for various reasons, and we settled on this neck of the woods. Weston, Wellesley, Wayland, Sudbury which were central to the Raytheon plants. You never really knew where you were going to get assigned, so it was a much better location than being way up in Wakefield. When I first came down here I worked in Sudbury. Will: Did they use microwaves, and radar? Harry: Yes, and there were great things that looked like bed springs up there on the roof that rotated around. They tracked targets and they had some fire-control equipment. Wayland, early on, was largely a plant where mostly navy programs were born. It was an engineering laboratory although we did make prototypes like the first model of something. Then the engineers figured out why it didn't work, then they fixed it and it got put into production.... Does Cobra Jane and Cobra Judy mean anything to you? Have you ever seen the big huge radar transmitters down on the Cape. There's one down there. They're gigantic. They look like a great big office building and they have a slanted face. In each one of those is a functioning element. Instead of rotating mechanically, they rotate electronically. Those type radars were built to protect this country from incoming missiles, and to track stuff up in space. That's what the unit on the cape does. They have one in Alaska. There's one carried on a ship. That was the height of the Cold War, when we were worried about missiles being shot at the country. That's what those were designed to track. Will: Do you know of any pollution that was given off by a laboratory in Wayland or Sudbury? Harry: Well, the energy from radar goes out. We would reduce power and see to it that the radar didn't hit the ground until a ways out. Nobody knowingly polluted the atmosphere or the ground or anything like that. Raytheon was responsible for what was determined pollutants. They've going through a great exercise digging down and hauling that stuff off the site. Will: Did Raytheon support schools or libraries or things like that? Harry: We certainly supported the schools. In Sudbury we would come down to the school. We would loan instruments to the physics and chemistry departments. We would come back and recalibrate them. We did that kind of thing. We would come down and listen to public speaking, and we would try to mark them on it. We came to the schools and helped training for academic decathlons. Raytheon donated money for the addition to the library. Will: Did you know anything about Raytheon before you started working there? Harry: Well, know. When we first came up to Boston, I was working for General motors. A division of General motors called new departure corporation. New departures made coaster brakes among other things. New departure made ball bearings. I came up here and worked for new departure and worked for places like MIT. I was an engineer so I'd go in and talk to the engineers and we'd talk about designs and loads and what not. Sometimes we'd give them sample ball bearings to use and some prototype. Ultimately that would come up with some kind of production. We would sell them ball bearings. In 57 and 58, there was a depression of sort. I was the last guy in so I was the first guy out. A friend of mine worked for Raytheon. He went to the naval academy and I knew him from there. I made some calls to him up at the Bedford laboratory. I asked if they could use another naval graduate, and they said sure come on up. That's how I got into Raytheon. I didn't really know much about it except that it was local. Will: Did Raytheon change the town? Harry: I expect it probably did. There were certainly local people who worked at the local plants, but there were people who worked down here that came from as far away as Chelmsford and practically Rhode Island. We had around 1900 people at max at the Wayland plant. And there were people from Sudbury and from Wayland who worked there. I know at one point on of the managers of the Wayland plant, I forget his name, he live here. There was connection with the town and we were sensitive to the fact that it was pretty tough with the traffic on route 20 when Raytheon was letting out, so we'd have guard and stop lights on route 20. So they would stop the traffic and valve people through. We tried to do support work with schools. Will: Did you like Wayland as a town? Harry: I loved it. That's why I'm still here. I'm on my third house in Wayland. Will: When did you retire from Raytheon? Harry: In 1989. Will: Did you work in Wayland up until you retired? Harry: I worked in Wayland for the last 5 or 6 years. Wayland and Sudbury were part of something called the equipment division, and Wayland and Sudbury were the equipment division laboratories. And we provided the engineering for the plant in Waltham and the one in Andover. They were all connected. Wayland tended to be a navy program. Sudbury started out as an air force facility, but it gradually cut out of that. In Sudbury we started to be in the missiles and space business. And air traffic control radars were a big thing in Sudbury. Between the two of us, we were the equipment division laboratories. The laboratory here was division headquarters. So a vice president of the company had his office in the Wayland facility. Will: Did Raytheon make you more worried about the Cold War? Harry: We were right in the middle of it. Mine personally was very involved in the ballistic submarine business. We were all kind of dumb. We all sat there with thousands of missiles. We had them the Russians had them, but nobody really wanted to use them. So it was a deterrent against starting a war. Because nobody was going to win a war that started with atomic weapons because you'd poison the world. So to some extent, the existence of those weapons probably prevented war. Will: Were there any times when you thought war was inevitable? Harry: There was always a threat. Does the Cuban missile crisis mean anything to you? That was a close one. We came pretty close to things getting out of control with that missile business, and that would have been terrible. Will: Was Raytheon a good place to work? Harry: Yes, yes it was. Will: At the time, did they give good salaries compared to other jobs? Harry: Oh yes. Probably better than some of the other jobs. They had personnel departments and human resources. The big difference was the position of women. Most of the women who worked at Raytheon were secretaries. Some of them worked as assembly people. Today, there are lots and lots of lady engineers which we didn't have back then. Will: Did you see Wayland grow from a rural town to a suburban town. Harry: Yeah, but it sort of snuck up on you. You didn't think much about what was happening. When we came here, the high school was here. The population was somewhere between 12 and 14 thousand people. When we came here, Wayland was very much a divided town between Cochituate and North Wayland. If you look at Wayland's history, the southern end of town was where the shoe factories were and where the people that went to work from 8 to 4 and got low wages lived. The northern end of town was farms and estates. Dan: Where there any complaints from the town? Harry: Certainly not noise because there wasn't any noise. Sometimes things like lighting at night, and when there was something we would try to do something about it. We would lower them or put metal shields over them. I'd say, in general, relations with the town were pretty good. The human resources people were very much interested in that kind of thing. As was I because I lived with the town. We tried to reach out to the town. A few of us would sit around with some of the higher powered folks in the company, and we would try to figure out what we could do to reach out to the town, to reach out to the kids, to reach out to the old people. Practically every year we had an open house. We would open it up, and people could go in.

|

Many citizens in the country were terrified that communism was spreading like a disease and that soon the Soviet Union may even attack America. They feared that the Soviets could launch a nuclear assault on America and its major cities via the northern reaches of the planet. In defense of this, the U.S. built numerous aircraft defense sites along the northern part of the country to shield them from any possible bomber attacks. One of the sites chosen to build one of these missile sites was North Wayland/Lincoln line in eastern Massachusetts.

Many citizens in the country were terrified that communism was spreading like a disease and that soon the Soviet Union may even attack America. They feared that the Soviets could launch a nuclear assault on America and its major cities via the northern reaches of the planet. In defense of this, the U.S. built numerous aircraft defense sites along the northern part of the country to shield them from any possible bomber attacks. One of the sites chosen to build one of these missile sites was North Wayland/Lincoln line in eastern Massachusetts.